Checker

Checker Marathon Cab NY by Fastlane Design 2011

If you grew up in or frequented any big Eastern city during second half of the 20th Century, you have seen a Checker. Probably you’ve ridden in one, most likely amid the mixed aroma of spiced meats, cleaning fluid and vomit. Drive one? Without a stint as a cabbie it’s not likely. But by happenstance in the summer of 1983, this writer did have the pleasure of driving a Checker, and without having to apply for a hack license. In between graduating from college, and starting my first “real” job, I worked as a chauffeur for a drive-your-car service in southern Connecticut. This was decades before Uber or Lyft. Then, when a driver was needed, we would be dispatched to the client’s house, and then chauffer them in their own vehicle to where ever they needed to go. Most every trip was to or from a New York area airport. Most every car was the ordinary fare of early 1980s suburbia; Oldsmobiles, Buicks, the occasional Honda. But one fine day the drive would not be to the airport, and the livery would be anything but ordinary.

The call came in from the dispatcher. Was I doing anything tomorrow? An old lady in Ridgefield wanted to go up to Bennington, Vermont to have lunch with her granddaughter. Vermont. A real drive. What a treat. On the way over there early the next morning I wondered what kind of car I would be piloting for the day. Not for a single moment did I imagine the freshly washed, dark green Checker Marathon I saw in the driveway as I pulled up to the house. A Checker! Who drives a Checker? My disappointment was fleeting, for my client, who was indeed ancient, was also charming. The day was lovely and so off we went.

Up through Connecticut and Massachusetts and into southern Vermont to Bennington is normally about a 2½ hour drive. This one took a bit longer. Once used to the glacial pace of 115hp trying to motivate 4000lbs of mass…and that I was driving a freak’n Checker…the car’s charms began to reveal themselves. The ride was terrific and I was surprised at how much road feel transmitted through that enormous steering wheel. The brakes felt strong and linear. Compared to the Impalas and Delta 88s I normally got to drive, the Checker’s chassis flex was non-existent, and there were few rattles. There would be no testing the Checker’s cornering capabilities, however. Not with a 75-year old lady perched on that flat rear bench seat, telling stories about her life.

In those days before SUVs, if you wanted a commanding view of the road, the front seat of a Checker was where you wanted to be. Indeed, that front seat was a very nice place to spend a morning. When I hoped out after over 3 hours behind the wheel, there was not a bit of fatigue. My elegant passenger, too, seemed no worse for the journey. As I took her hand and watched her alight through the tall wide door, I caught a glimpse of a by-gone day when passengers stepped out of a cabin, rather than unfold themselves from a compartment.

After handing off my charge to a quite lovely granddaughter, I turned to head back to the car to wait. There it was, standing tall and erect like a palace guard awaiting orders. Growing up an hour’s train ride from Manhattan, I’d seen hundreds, if not thousands of Checkers. They were as a part of the New York City landscape as skyscrapers and potholes. But this car wasn’t background. it had presence, she was beautiful. That freak’n Checker had won my heart.

(www.pineinterest.com)

Checker's Beginnings

Morris Markin

Checker founder, Morris Markin was born in Smolensk, Russia in 1893. He immigrated to America in 1913 where he settled in Chicago. A tailor by trade he would go on to make a fortune supplying uniforms to the U.S. army during WWI. Flush with cash after the war, he began to invest in Russian-owned businesses in the area. One of these was Commonwealth Motors, maker of the well-regarded Mogul automobile. Another was the Checker taxi fleet of Chicago. Markin merged the two in May of 1922 to form the Checker Cab Manufacturing Company.

1923 Checker Model C (www.coachbuilt.com)

The taxi industry in the 1920s was a violent business, especially in Chicago. It was ripe with corruption and bloody turf wars involving gangsters, teamsters and crooked politicians. To Morris Markin, survivor of Tsarist pogroms, it may have seemed tame. Still, when a firebomb was tossed at his home as part of a labor dispute, he deemed it prudent to move Checker’s manufacturing operations from Chicago 150 miles east to Kalamazoo, Michigan.

The first cab made by Checker in Kalamazoo was the 1923 Model C. This was a beefed up version of the Commonwealth Mogul. Designated the Model C, it proved very popular with taxi fleets, especially in New York.

Markin proceeded to set up a complex web of operations that was vertical integration at its most opaque. The Checker Cab Manufacturing Company built the cabs, while a series of sales and distribution companies, all controlled wholly or partially by Markin, sold them to taxi fleets in cities from Minneapolis to Boston, especially Chicago and New York. Another of his companies, General Transportation Casualty, insured them. Business was good.

The First True Checkers

1928 Checker Model K (www.Coachbuilt.com)

While the Checker Model C was essentially a carry-over passenger car, the all-new for 1928 Model K was a purpose built cab. In the 20s and 30’s taxis were conveyors of the upper classes. Working class folks were relegated by economics to the streetcar or bus. As such, taxis were large, richly appointed coach-built cars, limousines for hire that trolled the financial districts and toney neighborhoods for well-heeled fares. Many cities required that cabs be able to carry eight passengers. The Model K served this market well. Its style and comfort, sturdiness and reliability, pleased passenger and operator alike. Checker quickly became America’s cab of choice, a distinction it would hold for another half a century.

1932 Checker Model M (www.coachbuilt,com)

The dawn of the 1930s brought the new Model M, with radical new styling on a slightly modified K chassis. The rectangular Woodlite headlamps made Checkers cabs easily identifiable at night. The scooped front fenders were designed to reduce the cost of fender benders. Less fender to bend.

The 1930s also brought Checker’s first financial setback. At the Depression’s nadir in 1932, the company lost over $800,000. Morris Markin had made some enemies in his 10+ years in the taxi business. The Checker board of directors took this opportunity to remove him as company president. But Markin had survived Tsarist Russia and the mean streets of Chicago. He would survive a little boardroom brawl.

1934 Checker Model Y (www.checkerworld.org)

Some years earlier, Markin had met E.L. Cord when the latter was selling cars in Chicago. The two maintained a friendship as both saw their business empires expand. Cord was now a titan in the automobile industry, owning Cord, Auburn and Duesenberg, as well as Lycoming Engines and the Saf-T-Cab Company of Cleveland, OH. After his ouster, Markin turned to Cord, and convinced his friend to take a controlling interest in Checker. And, of course, to reinstate Markin as president. The partnership resulted in Checker using Cord’s new Lycoming 115hp strait-8 engine in the upcoming Model Y, as well as adopting some Auburn styling cues.

By 1936 E.L. Cord had run afoul of the new Securities and Exchange Commission. Markin took the opportunity to buy back his stake in Checker Cab Manufacturing. It is hard to say whether Markin saw the writing on the wall, or somehow helped to write it, but by the close of 1937, Cord’s automotive holdings were bankrupt, while a newly independent Checker was going strong.

The Checker Model A debuted in 1939. The Lycoming engine was dropped in favor of a Continental-supplied 226 cu. in. Red Seal 6-cylinder engine. This engine would power Checkers for the next quarter century. But it wasn’t Checker’s new engine that caught people’s attention. The Model A was not only the most outrageous looking Checker, but it may have been one of the strangest looking American cars ever. Large oval headlamps surrounded by gaudy chrome shields, and separated by a body color waterfall grill and a plunging beak, form a face that defies a search for adequate adjectives. Trying to track its creator brings to mind the adage; success has many fathers, while failure is an orphan child. No designer working for Checker at the time claims responsibility for this ugly bastard. But if you were trying to hail a cab in 1939, you knew more than a block away that a Checker was coming.

1939 Checker Model A Landaulet

The Model A remained in production until 1942, when the nation’s industrial might was converted to serve the war effort. Checker won contracts to build self-contained trailers, truck cabs and a massive tank recovery vehicle. The company also bid on the army’s ¼-ton reconnaissance vehicle which would later be known as the Jeep. Four prototypes were built, but the contracts went to Willys and Ford.

As the outcome of the war gained clarity, Checker engineers in Kalamazoo got to work on a new Cab. They experimented with a couple of unconventional designs meant to maximize interior volume while minimizing exterior dimensions. One prototype used a rear-engine, rear-drive setup, the other had a front engine and front-drive. When testing began, the former was quickly dismissed because of handling problems caused by rear weight bias. The front-driver got a bit further. It proved however to be too expensive to produce and not robust enough for taxi duty. But the look of the car was impressive. Noted coach designer Ray Dietrich had been commissioned to do the car’s body. The front was forward thrusting in order to contain the now non-existent FWD running gear. Called the Model A-2, it was unique looking like the previous Model A, but pleasing and modern. You still knew a Checker cab was coming, but now you weren’t horrified when it arrived.

1950 Checker Model a-2 (checker ad circa 1950)

Birth of an American Icon

Since 1929, New York City required that any taxi or limousine carry at least 5 passengers in the rear. Prior to the war, most manufacturers produced such a car. By the early fifties, only DeSoto and Checker where left. Nearly three quarters of all Taxis in New York and Chicago were now Checkers. But the NYC laws were changed in 1954, and now standard four-door sedans were permitted for taxi use. Moreover, to reduce congestion taxis were limited to a 120-inch wheelbase. The big cabs that formerly roamed the city’s streets would soon be banned.

To meet these challenges, work began on the first truly all-new Checker in three decades, the Model A-8. This was a thoroughly modern car. Independent coil springs took the place of the ancient I-beam front axles. It was mounted to a new heavy-duty X-frame chassis. The A-8 still used the Red Seal Six, but it had been reconfigured for higher compression and more power. Automatic transmission, power steering and power brakes became available for the first time in a Checker.

Checker A-8 prototype (www.checkerworld.org)

X-frame chassis (www.checkerworld.org)

Vehicles for taxi use had to be both durable and serviceable. The A-8s X-frame chassis was purpose built to take the punishment without shakes, rattles or rolls. Its fenders were attached with 12 bolts and could be replaced in 20 minutes. Identical front and rear bumpers reduced cab operator’s repair and inventory costs. Extra hard brake lining greatly increased time between adjustments or replacements. All of the under-hood components in the A-8 are located up high in the engine compartment for quick easy servicing, and away from splashing water.

Durability was important for taxi operators but comfort and convenience are first and foremost for passengers. To allow fares to easily get in and out, the A-8s doors were wide and square and at least 5 inches taller than an ordinary sedan. You stepped into a Checker while you folded into a Ford or a Chevy. A two-piece drive shaft eliminated the need for a transmission tunnel and allowed for a flat floor. The rear seat was pushed back between the rear wheel wells. Combined with a 120” wheelbase, the car had over a foot more leg room than an ordinary sedan. The extra space allowed for optional jump seats, stretching seating capacity to eight. Checker interiors may have been larger than some New York City apartments!

more room than some nyc apartments (www.checkerworld.org)

And for the first time a Checker could be ordered for private use. Not that it was simple for Joe Public to get one. He had to contact a zone sales office to arrange a test drive, and then fill out an order sheet. Servicing was a little easier as it could be performed at any taxi garage that operated Checker cabs.

The next few years brought incremental changes. In 1959, Checker introduced the Model A-9 that had quad sealed-beam headlights, creating a look that would be virtually unchanged for the next 16 years. Also that year, Morris Markin decided to offer Checkers to the public more vigorously. He set about building a small dealer network. The private model was called the Superba, and it helped move almost 5800 Checkers in 1959, a 76% increase over the previous year. While this was barely a day’s production for GM or Ford, for Checker, whose breakeven point was just 2000 cars, it was immensely profitable.

the iconic checker Cab (www.checkerworld.org)

On that drive up to Vermont I mentioned to my client that I’d never driven a Checker before, and that it was quite a fine car. “We had had a Packard before this,” she said. “They stopped making Packards. A shame.” Did she know what year this car was? “Oh we’ve had it a long time, since before my husband passed.” She recounted the day they took the train into New York to get it. There was shopping and lunch first. It was an event. But why a Checker, asked 22-year old car-guy me. She told me they had liked it because you felt safe driving it. “And you can see out of it,” she said, looking out the window at the New England scenery, “Like you could in the old Packard.” I never did find out what year the car was. With a Checker, I suppose it didn’t much matter.

1961 Checker Station wagon (www.coachbuilt.com)

In 1960, Checker introduced its first station wagon. It had a two-piece tailgate for versatility. The rear seat folded down for a 109” x 49” cargo floor, far more than any other passenger car on the market…or a modern Chevy Suburban for that matter.

Nineteen sixty-one brought an updated A-10. It had a more powerful OHV six, and debuted the venerable Marathon nameplate.

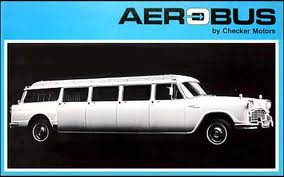

1962 Checker aerobus (www.checkerworld.org)

More new models arrived in 1962. The X-frame chassis was well suited to be extended without significant loss in structural rigidity. The Checker Aerobus wagon came in 6-door, 9-passnger, and 8-door 12-passenger configurations, adding either 34 ½ or 69 inches to the wheelbase. Both used a Chevrolet sourced 327 cu in V8 engine. Airport shuttle drivers could boast that it had a Corvette engine, and in the broadest sense they were right. The massive 12-passenger Aerobus was 270 inches long, giving it the distinction of the being the longest regular production passenger vehicle ever made.

1962 checker limousine (www.checkerworld.com)

A new limousine appeared in 1962, with an extra nine inches of space in the rear than an already roomy ordinary Marathon. The jump seats could be converted to a bench allowing for 6 passengers in back. The limousine had much richer appointments and a glass partition. Several were sold to the State Department after U.S. ambassador to Moscow, Llewellyn E. Thompson advised Washington that the existing Cadillac livery was, ”…not suitable for the cobblestones and rough roads encountered in the Soviet Union.” They were no problem for the Checker.Decline and Fall

Throughout the 1960s, the taxi market in America wasn’t huge but it was steady. Checker made the roomiest, most rugged car around. They had little competition. Freed of the need to make frivolous changes every year – or decade – to stay competitive, engineers were freed to focus their efforts on reducing costs through manufacturing efficiencies. The result was that Checker Motors delivered consistently strong profits selling 5000+ cars per year every year with minimal changes.

federal regulations were not kind to checkers

It wasn’t until 1975 that government mandated safety regulations brought the first noticeable change to the Checker’s appearance in a decade and a half. The simple chrome bumpers were replaced with a pair of massive steel girders that looked like repurposed freeway guardrails.

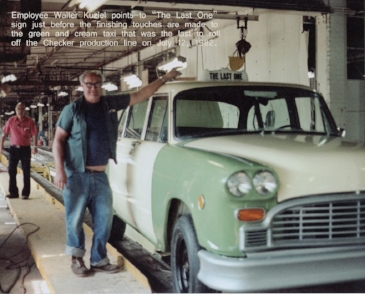

In 1981 Checker Motor Company’s 48-year streak of profitability was broken when they booked a loss of nearly half a million dollars. Ever more oppressive federal regulations, combined with a stagnant economy, was extracting a heavy toll, and no letup was in sight. David Markin had been running the company since his father Morris’s death in 1970. He asked UAW workers at the Kalamazoo plant to accept concessions on pay, otherwise he would be forced to shut down automobile production. They didn’t, he did, and the Checker cab was no more. When production ceased on July 12, 1982, the New York Times ran an obituary with the headline, “Checker Cab, 60, Dies of Bulk in Kalamazoo.”

the last checker (www.checkerworld.org)

It took another 17 years of hard New York City driving to lay the final working Checker to rest. Cabbie Earl Johnson decided that on July 26, 1999 he and his 1978 Marathon would retire. With nearly 1 million miles on the odometer, the cab Mr. Johnson named “Janie,” after an old sweetheart, required $6,000 in upgrades to meet ever-stricter city regulations. Said one of the passengers interviewed on that last day, “The Checker is the ultimate luxury. It’s such a grand car. It’s a vehicle that belongs to New York.”

While in 1982, Checker stopped building the cabs it was known for, the company soldiered on, profitably supplying body stampings for General Motors and others. But in 2009, Checker found itself caught in the vice of the financial meltdown, and was forced into bankruptcy after 88 years of operation.

Back in New England on that summer day in 1983, the return trip to Connecticut was just as lovely as the drive up. It was quieter though. My elderly passenger was tired from an eventful day. That gave me more time to appreciate the majesty of this fine car. It was a rolling monument to the idea that, while change is inevitable, it isn’t always better. I shall never forget and always be grateful for my wonderful day with a Checker.

photo by high gravity photography (www.highgravityphotography.com)

copyright@2019 Mal Pearson

Checker Resources

Checker World www.checkerworld.org

Checker Parts www.checkerparts.com/