Stutz

For more than 20 years during the early part of the last century, Stutz was a builder of some of the finest automobiles in the world. Like so many of America’s classic marques - Mercer, Marmon, Pierce-Arrow and Duesenberg – Stutz was felled by the Great Depression. But Stutz alone would experience a rebirthing. More than three decades after its untimely demise, the venerable name was once again spelled out in chrome. For its second coming, however, Stutz automobiles were decidedly less distinguished.

Part I: The Legend

Hollywood’s first great car movie was Cecil B. DeMill’s, The Roaring Road. The hero in this 1919 silent classic is a dashing young race driver named Walt “Toodles” Walden, played by, Wallace Reid. On the screen and in real life, Reid was identified with fast cars. Think of him as the Steve McQueen of the silent era. The movie has Reid’s Toodles striving to satisfy not only his need for speed, but his desire to win the hand of a beautiful girl. And the plot thickens. That girl just happens to be the daughter of Toodle’s employer, J.D. Ward, a wealthy car company tycoon. The film’s climax has our hero roaring down a country lane in what looks to the modern viewer like an old jalopy, albeit a very fast one. Toodles is racing a train to a crossroad, the last hurdle on his quest to set the speed record from Los Angeles to San Francisco, and winning the hand of the tycoon’s daughter in the process. Even today one is gripped by the speed of both car and train. The roar would be deafening…if there were sound. What is that 100-year old car, we wonder, and how does it not shake apart as it speeds over that gravel country highway? The car is a Stutz, one of the great names of the automobile’s early years.

Paramount Picture’s, The Roaring Road, staring Wallace Reid and a Stutz Bearcat (www.imcbd.org)

Harry Clayton Stutz was born in 1878, an Ohio farm boy who took a shine to mechanics. As soon as his chance came he moved to Dayton where he took various jobs working on machines and learning his craft. By the age of 22, he had built a fairly sophisticated 1-cylinder car that would open doors for him in the budding automobile industry. He moved on to Indianapolis, a city that at the time was rivaling Detroit as America’s auto-making capitol. After a number of positions over the next few years, Stutz became chassis designer at the American Motor Company of Indianapolis, makers of the groundbreaking American Underslung. Unlike its contemporaries, the Underslung’s axles were mounted above the frame, allowing a much lower center of gravity for better handling.

1906 American Underslung (www.cruise-in.com)

By 1910, Harry Stutz had moved on to found the Stutz Auto Parts Company in order to build a patented rear-mounted transaxle he had designed. By the following year, Harry had mated this durable and compact 3-speed gearbox with a powerful Wisconsin T-head 4-cylinder engine, and installed them in a lightweight, low slung chassis. The result was a potent racing car which he entered the inaugural 1911 running of the Indianapolis 500.

Cal Anderson's Stutz Bearcat at inaugural Indy 500 (www.Trackforum.com)

Piloted by Cal Anderson, the #3 Stutz car finished in 11th place. That doesn’t sound so hot, except that nearly half of the 40 cars entered didn’t finish at all. The Stutz also was the only competitor that was not a purpose-built racing car. Indeed, Harry was taking orders for his upcoming 1912 Stutz Series A, for which his entry was the prototype. The Series A would consist of the Bulldog Tourer, the Inside-Drive Coupe, and the Bearcat Speedster. The last of which, other than some cosmetic changes for production, was identical to the car that crossed the finish line at Indy the year before. It is the Bearcat for which Stutz will forever be remembered with a smile.

Stutz Bearcat a painting by Bill Sims

Bearcat. Has there ever been a cooler, more visceral name for a car? It conjures up a wild cat mauling the throat of a hulking bear. The imagery is appropriate. The Stutz that competed at the first Indy 500 had a 6.3-liter engine. Big by today’s standards, but every other car at Indy in 1911 had engines displacing from 7.1 to 9.7-liters. Doing the job with agility over brute power, the Stutz truly was a cat hunting bears. At least one Bearcat was entered into 30 different races in 1912. Twenty-five time times one of them finished 1st.

1919 Stutz Model R Bearcat (www.Pineinterest.com)

The Bearcat’s notoriety on the race track bred success in the marketplace. Stutz became a highly sought after car by the sporting set. By 1916, Harry Stutz was attempting to capitalize on his car’s winning ways by taking the company public. As it turns out, he was a much better engineer than financier. He lost control of the company to a stock manipulator named Alan A. Ryan. Stutz stayed on as president under Ryan for a few more years, before he departed to once again be his own boss.

But not before he introduced the beautifully updated 1917 Model R. Unique for its day, the R’s engine had 4 valves per cylinder. It was also Stutz’s first power plant to be designed and built in-house.

Harry C. Stutz (www.FindaGrave.com)

Harry C. Stutz’s new company, H.C.S. Cars, was incorporated in 1920. It built much the same sort of car as his old company, expensive machines that leaned to the sporting side. An H.C.S. special even won at Indy in 1923. In 1924 H.C.S. shifted its attention to building taxis and fire trucks, thought to be more profitable. This strategy proved ill-advised. H.C.S. went bankrupt in 1927. Harry succumbed to a burst appendix in 1930.

Harry Stutz had been a perfectionist, and as such Stutz Motors always stood behind the performance of its cars. In early 1919, a disgruntled owner brought his Bearcat back to the distributor complaining that the car was “gutless,” causing him to be bested on the streets of New York by a rival in a Mercer Raceabout. The Stutz publicity department seized on the opportunity. With much fanfare, it handed the offending Bearcat over to renowned long-distance racer/promoter, Cannonball Baker. Baker then roared off on an 11 day, 7 ½ hour quest (on unpaved highways) to successfully set a new trans-continental speed record. The real life behind The Roaring Road.

Wally Reid in a Stutz (www.imcbd.org)

Stutz sold its 10,000th car in 1919. That same year, in a karmic twist, the stock manipulator Alan Ryan himself lost control of Stutz. Capitalist Charles Schwab, who’s day job was running Bethlehem Steel, was now in charge of the famed sport car maker. Stutz was a nice plaything for Mr. Schwab, but he knew very little about performance cars. It wasn’t long before the company lost its engineering edge. Sales dwindled.

1926 Stutz Series AA Blackhawk (www.HeacockClassic.com)

By 1925, Schwab had hired a gunslinger of a new chief executive named Fred Moskovics to revitalize the storied marque. Moskovics immediately shut down production of the Series R and hired Swiss engineer, Charles Greuter, to design a completely new line of car. The Stutz Series AA was powered by a sophisticated new overhead cam, dual-ignition “Vertical-Eight” engine.

Sadly, with the AA’s debut, the Bearcat name got the axe. Moskovics had decided to pivot away from the hairy-chested minimalist racers on which Stutz had made its name. He focused instead on elegant grand tourers like the smooth and powerful successor to the Bearcat, the Blackhawk Speedster. With its thrusting hood, side mounted spare, and rakish boat-tailed rear, the Blackhawk was one of the most beautiful cars on the road. With Greuter’s powerful Vertical-Eight engine, it was also one of the fastest. Stutz sold 5,000 cars in 1926, its best year ever.

By 1928, the competition had caught up to Stutz. Sales of the AA began to wane. Moskovics countered by returning to racing in a big way. The endeavor had mixed results. That year a team of three race-prepared Stutz Blackhawks challenged at LeMans. One of them placed 2nd behind one of the mighty 4 ½ liter Bentleys. It was the best showing for an American carmaker at Circuit de la Sarthe until the Ford GT40 placed 1-2-3 in 1966. Unfortunately for Stutz, a crash at Daytona, an embarrassing engine failure in a prize race with Hispano-Suiza, as well as several other high profile promotions, all ended in failure. The company’s reputation was seriously damaged. By 1929, Stutz was losing $2.5 million annually, driving Moskovics out of a job.

1932 Stutz DV-32 Victoria (www.Kimblestock.com)

Then came the Great Depression. Sales continued to plunge while losses soared. The response from Stutz’s new management was to continue focusing on performance and style, and let the Stutz cachet speak for itself. The performance side of this equation was a new Greuter-designed eight-cylinder engine called the DV-32. Duesenberg had recently seized the role of top dog in the performance car market. So like Duesenberg, the DV-32 was a 4-valve per cylinder DOHC design that pumped out 161hp. That was about 100hp less than the supercharged Duesy, but it was still quite a bit more than just about anything else on the road. For style, Stutz called on coach builders like Rollston for gorgeous bodies like the show-stopping Victoria.

1932 Stutz DV-32 Super Bearcat (www.UniqueCarsandParts.com.AU)

The efforts weren’t enough. Competitors like Cadillac and Packard were introducing twelve and even sixteen cylinder engines. While these great behemouths couldn’t match the much lighter Stutz’s overall performance, the allure of more cylinders claimed much of what little was left of the prestige car market. Stutz had no funds to develop new engines. Its final gasp was a stunning interpretation of the original legend, an aluminum bodied DV-32 on a shortened wheelbase called the Super Bearcat, in this writer’s opinion, the most beautiful car of the 1930s not made in France.

Even Toodles Walden’s high speed escapades on the roaring road wouldn’t have been able to save Stutz. It sold just 310 cars in 1932, and a mere 80 in 1933. Only 6 were sold in 1934, before the storied marque slipped beneath the waves of the Depression.

Part II: The Second Coming

Stutz wasn’t the only prestigious marque brought down by hard times. Mercer, Marmon, Pierce Arrow and Duesenberg all built their last car during the 1930s. The great Stutz name rested in peace for three decades. Then in late-1963, more than a generation after the great classics roamed the American road, noted automotive writer Diana Bartley approached Esquire Magazine with an idea. Wouldn’t it be cool to see what those cars might look like if they were made today?

Bartley enlisted famed stylist, Virgil Exner, to render four modern interpretations of the most storied marques of the past. Exner had recently been fired as chief of design at Chrysler Corporation for the poor showing of his early 60s cars. Many claim he was scapegoated for the incompetence of senior management. Either way, Ex was anxious to redeem himself. He did 4 pencil drawings for the Esquire piece. They were visions of what a 1964 Packard, Mercer, Duesenberg and Stutz might look like if they were still in production. These became known as the Revival Cars.

Packard

Mercer

Duesenberg

Stutz

Exner with his prototype for a new Duesenberg (www.CarConceptz.com)

Nothing much came of the first two, but Fritz Duesenberg, son and nephew of the founding Duesenberg brothers, along with a group of other investors were inspired. They enticed Exner into joining them in an effort to revitalize the Duesenberg name. Exner probably didn’t require a hard sell, the Duesenberg being one of the great Classic Era cars he so admired, and drew upon for inspiration throughout his career. The Duesenberg revival was very close to getting the green light when a key backer suddenly pulled out. The project was aborted. After working hundreds of hours on the designs, Ex was devastated.

But not for long. One of the original Duesenberg investors, a financier and fancier of fine cars named James McDonnell, was undaunted. He was still convinced that there was a profitable market for a low-volume, ultra-luxury car that could be built using an existing mass production chassis and drivetrain. But what to call it? Fritz Duesenberg retained the rights to his storied family name, and he was no longer interested in the scheme. But further research revealed that Stutz was now considered part of the public domain.

Exner jumped at the chance to pen a modern Stutz Blackhawk. His new design borrowed the stillborn Duesenberg’s formal sedan roofline and backlight and its upright grill. These elements were combined with the graceful 2-door body of the 1964 Stutz revival rendering. All they needed now was a suitably sleek platform on which to build the car.

1969 Pontiac Grand Prix SJ

At about the same time, John Z. DeLorean, the dynamic new general manager at Pontiac, was preparing to introduce the first ever midsized personal luxury car. Exner had seen early photos of this upcoming 1969 Pontiac Grand Prix and was intrigued. The proportions were very much in harmony with his classical baroque themes.

The proposal Exner and McDonnell would present to DeLorean was of an elegant hardtop coupe. It was as garish as those Olympic chariots of the early 1930s that Ex so adored. Never shy for publicity, DeLorean must have figured this opulent Stutz might lend his new Grand Prix a bit of cachet. He agreed to supply Stutz with its donner cars. Love it or hate it – there really is no in between – the result was the 1970 Stutz Blackhawk.

1970 Stutz Blackhawk prototype (www.madle.org)

While production numbers would be small, the Blackhawk’s assembly line was as long as it gets. Starting in late-1969, very small batches of Pontiac Grand Prix were shipped from their Detroit factory to a contract builder in Italy called Padane, who also did bodies for Maserati. In addition to making the Blackhawk’s enhanced bodywork, the coachbuilder fitted the cars with the finest luxuries money could buy. There was Australian lamb’s wool carpets and English leather upholstery, Birdseye maple inlays and 24 karat gold trim. All that grander added up to an eye-popping price tag of $26,500 - which was about 4 times the price of the Pontiac it once was.

The first series Blackhawks (1970-71) could be identified by their split windshields and lack of a rear bumper. Squinting a bit, one can even see the visual lineage to the beautiful 1932 Stutz Victoria and Super Bearcat. Those first 27 cars were also the only Stutzes equipped with Pontiac’s 428cu in 425hp Super Duty V8 engines. These monster motors propelled the 5,000lb car from 0-60mph in 8.5 seconds, topping out at 130mph. Fuel economy was 8mpg… if you’re keeping score.

Most Stutz buyers were not. Like one of Virgil Exner’s earlier creations, the Dual-Ghia of the mid-1950s, Blackhawks found their way into the garages of the rich and famous. Dean Martin and Sammy Davis, Jr. were early Stutz owners. As the story goes, Frank Sinatra was offered the first production Stutz in exchange for publicity considerations. To which, Ol’ Blue Eyes politely told them where they could stick their endorsement. The car, and the arrangement, were then offered to Elvis Presley, who immediately agreed. Sinatra was livid. He would never own a Stutz, even though the rest of his infamous “Rat Pack” brethren drove them.

Dino might have been a repeat buyer (www.curbsideclassic.com)

Elvis, on the on the other hand, loved his Stutz. He bought 3 more over the years, including the car he was photographed driving off to meet his “pharmacist” on last day of his life.

Elvis takes delivery of the first Stutz Blackhawk (www.MotorJunkie.com)

Farewell to the King

Liberace and the Stutz, made for each other (www.Pictagram.com)

After 1972, production moved to Carrozzeria Saturn in Cavallermaggiore, Italy. As the 1970s progressed, the Pontiacs on which Stutzes were based grew more bulbous. And so, much like The King himself, the Stutz did too. By 1980, the Blackhawk coupe and IV Port sedan were being built on a full sized Pontiac, and later Oldsmobile chassis. Despite their car’s less flattering proportions, the company consistently sold about 50 a year from the mid-70s through early 80s. Isaac Hayes, Wayne Newton and Liberace - all well-known models of restraint - were Stutz owners.

A storied mark devolved into pimpmobile duty (www.imcdb.org)

As far as Stutz’s movie career? Oh how the mighty hath fallen. Back in 1919, when the Cecil B DeMill needed a car that evoked power and speed in Roaring Road, he chose a Stutz Bearcat. When the makers of the rather lame 1982 comedy, Night Shift, needed a suitable pimpmobile for two morgue workers moonlighting in the flesh trade, they chose a Stutz IV Port.

A limousine called the Diplomatica was offered for a time. It sourced Cadillac Fleetwood underpinnings and looked like a bad acid trip. In total, seven of these beasts were produced, all custom made for their buyers. Only one was sold outside the royal families of the Arabian Peninsula. One particular gold-trimmed, bullet-proof Diplomatica sold for $550,000. At the time, it was the most expensive production car ever built.

Stutz Diplomatie: a favorite of the Saudi royal family (www.madle.org)

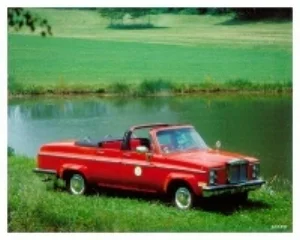

Taking advantage of a royal taste for Stutz, the company converted 46 Chevrolet Suburbans into parade cars called Bears. All of them were sold to the royal guards of the both Saudi and Moroccan kings. They look robust enough to guard against the shockwaves caused by Harry Stutz rolling in his grave.

An atrocity: the Stutz Bear (www.madle.org,)

The last car to carry the Stutz name was the 1987/88 Bearcat II. It was based on the Pontiac Firebird, and had a body made of dent-proof carbon fiber, reportedly the same material used in the stealth bomber. The first 2 car went to the Sultan of Brunei.

1987 Stutz Bearcat II (www.madle.org)

When the Bearcat II was introduced at the Monte Carlo Auto Show, reporters were given hammers and invited to whack at the body to their hearts delight. Unlike Elon Musk’s hammer malfunction at his Tesla Truck unveiling decades later, no damage resulted. Few Bearcat IIs resulted either - only 13 were made in all.

Tesla window malfunction (www.Motor1.com)

The Stutz Motor Company is technically still in business. Once in a while it even manages to sell a “new” car to some rabid Stutz-o-phile. It is unclear whether these were refurbished older cars, or were pulled from some secret inventory of stashed Stutzes.

All totaled, 35,000 of the original Stutz roamed the roaring roads of the early 20th century. They will always be cherished by collectors, and remembered by historians as the first great American sports cars. The second coming of Stutz produced 617 vehicles (and counting?) from 1970 through the early 1990s. It is perhaps fair to say that the collective automotive memory may not hold these reinterpretations with the same reverence as their forbearers.

Copyright@2020 by Mal Pearson

Sources

The Standard Catalogue of American Cars: 1805-1942 by Beverley Rea Kimes and Henry Austin Clark, Jr.

The Standard Catalogue of American Cars: 1945-1975 by Ron Kowalke

Hemmings Classic Car May 2016 Stutz: Speed with Style by Patrick Foster

The Old Motor www.TheOldMotor.com

Unique Cars & Parts www.UniqueCarsandParts.com

Stutz Motor www.stutzmotor.com

The Stutz Club Online www.stutzclub.com

The Internet Guide to Stutz www.madle.org