Willys-Overland

Willys Overland is best known as makers of the original Jeep. With good reason. That little truck helped win a world war. The parent company, however, predated its famous aspiring by 40 years, holding a memorable place in its own right in the annals of automobile history. The original Overland of 1902 was one of the very first cars to employ the front engine, rear drive layout that would become the industry standard for the next half century. Willys was the second bestselling car in America during the 1910s, still #3 by the late 1920s, and its strong performing compact cars of the 1930s dominated that category decades before anyone thought to give it a name. The Willys brand did not survive the industry’s post-war consolidation. But through the Jeep name, passing though no fewer that 7 owners, and counting, the Willys-Overland soul lives on.

A Rocky Beginning

1904 Overland runabout (www.RMauctions.com)

Willys-Overland was born in the infancy of the American automobile industry. The Olds Curved Dash had just burst onto the scene. Its tremendous acceptance by the general public convinced many an industrial visionary that there was a bright future in the automobile. Two of these of these were Charles Minsall and Claude Cox. The former was managing director of the Standard Wheel Company. Minsall smelled big profits in automobiles, even though he knew nothing about the contraptions himself. Cox was a young engineer who had built his first motorcar as a senior thesis at the Ross Polytechnic Institute. Minsall had heard good things about Claude Cox and hired him to design and built a car for the newly created automotive division of Standard Wheel.

It was called the Overland, a runabout like the Olds Curved Dash. Unlike the Olds, and most other early cars, the Overland’s 2-cylinder water-cooled engine was mounted up front rather than under the seat. This configuration would soon become the industry norm. Unfortunately, the Overland’s engineering excellence did not extend to Standard Wheel’s ability to manufacture and sell it. Eighty-two Overlands were built in 1903-05, none of them at a profit. Charles Minsall decided he had had enough of the red ink. Just as Cox was readying to produce a larger 4-cylinder model, he was informed that Standard Wheel was no longer interested in making cars. Had the Overland story ended here it would not have been an uncommon experience. During the first dozen years of the industry, hundreds if not thousands of startup carmakers passed into the annals of obscure history books.

Claude Cox (www.Hemmings.com)

But the Overland story did not end here. A successful carriage maker named D.M. Parry was a major customer of Standard Wheel. Wanting to get into the automobile business himself, and admiring Claude Cox’s work, Parry stepped in to save the day…almost. In exchange for 51% of the new Overland Auto Company, Parry would finance a resumption of operations at a plant in Indianapolis. Production was about to begin when the Panic of 1907 swept the nation. It washed away much of Parry’s fortune, leaving Overland Auto high and dry. Claude Cox found himself with a partially built factory, a pile of parts, several hundred workers, and no money to pay for any of it. The days looked dark for Overland, but another savior would soon appear.

A Salesman and a Visionary

John North Willys (www.allpar.com)

John North Willys was raised in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York. John was a salesman and an entrepreneur from an early age. He opened a laundry business in 1888 at the age of 15 and sold it a year later for a thousand-dollar profit. His father urged Willys to use this windfall to study law, a field in which he had no particular interest. Upon his father’s death a few years later, Willys quit the law and in 1892 he became a bicycle distributor in his hometown of Canandaigua, NY. Four years later he had expanded to Elmira. Soon he was selling out the entire production of several bicycle factories. By 1900 his businesses had annual revenue of half a million dollars.

Willys saw his first automobile on a business trip to Cleveland, OH in 1899. He noted the intensity in which crowds viewed this new machine. An astute observer of business trends, Willys concluded that the automobile would one day replace the horse - as well as the bicycles he was now making - as America’s first choice in personal transportation. Within a year he had become a dealer for the Pierce automobile. He managed to sell 2 cars. Undaunted, he took on a franchise for the new Rambler, built by The Jeffrey Co. of Kenosha, Wisconsin. Willys sold 8 cars in 1902. When riding a wave of the future, to achieve success one must be both opportunistic and patient. John North Willys was both. He sold 20 cars in 1903.

Americans were becoming steadily more aware of the automobile. The excitement and freedom car ownership offered was beginning to erode their skepticism. By 1906 Willys was casting about for expanded opportunities. He wanted more than just a new car to sell, but rather one good carmaker for which he could become sole distributor. In the Overland Motor Company of Indianapolis, he thought he had found what he was looking for. Willys paid $10,000 as down payment on a contract for 500 cars – what was to be Overland’s full production run. After many weeks waiting for his cars and a number of unanswered telegrams and telephone calls, Willys was getting anxious. He boarded a train for Indianapolis to find out what had happened to both his order and his money. Upon his arrival at the Overland factory, he found no activity, a few partially-built cars, and one distraught Claude Cox, just recently stripped of his financial backing. Most men would have walked away from the mess and written off their loss. Most men did not have John North Willys’ optimism and drive.

1908 Overland (www.earlyamericanautomobiles.com)

Using his skills of persuasion, Willys first convinced the firm’s creditors to put him in charge of the operation. He then set out to recapitalize the company. He talked suppliers into granting him 90-day terms as he reorganized the factory. Mr. Willys wasn’t afraid to roll up his sleeves and get his hands dirty. The factory workers respected him for that. It didn’t hurt that he also made sure all of them who stayed on received back pay plus a loyalty bonus. Willys was able to revive Overland’s production and sell 46 cars in 1907. Then he sold 465 in 1908. Overland Motors was reformed as the Willys-Overland Company and earned a $50,000 profit that year.

The new company’s soon found itself constrained by production limitations. So much so that a circus tent had to be set up nearby to house a makeshift expansion. Thus, when a factory in Ohio came up for sale the following year, Willys jumped at the opportunity. All production was moved to Toledo, where descendants of Willys-Overland’s products are still built today.

1910 Willys-overland model 38 (www.allpar.com)

Some of Mr. Willys’ actions, especially the move to Toledo, did not sit well with his chief engineer, Claude Cox, who resigned in anger. Willys, however, owned the company, which owned all the patents, making Cox expendable.

The first Toledo-built Willys-Overland debuted in 1910. It was called the Model 38. Nearly 16,000 of them were sold that year. By 1912, sales had doubled to 32,000, making the Overland was the #2 selling car in America. The Model 38 used a sliding gear transmission pioneered by Packard making it simpler to drive than the #1 selling Ford Model T with its planetary box. The Overland was more expensive than the T, but it also enjoyed a better reputation for quality. By 1916, Willys’ sales surpassed 142,000, which was good for nearly 10% of the 1.5 million cars sold that year.

Rapid Expansion

During the next decade, John North Willys went on a buying spree, greatly expanding his business empire. He bought Gramm Motor Trucks, which in 1913 would begin producing the first vehicle to carry the Willys name. Soon after Willys entered the premium car market. On an ocean journey to England, Willys met an engineer names Charles Knight. Knight had developed a new valve design that was far smoother than traditional engines. They talked extensively about the benefits of what Knight called his “sleeve valve,” which allowed for a much smoother operation by replacing the traditional and rough running poppet valves with precision sleeves to control intake and exhaust.

The Knight Sleeve-Valve engine (www.wikipedia.com)

Upon reaching England, Willys hired a car equipped with Knight’s sleeve valve engine and proceeded to log 4,000 miles over the island’s primitive road system. He returned to America impressed and motivated. He commissioned a new luxury car called the Willys-Knight in 1914, a fine car that would compete with the likes of Cadillac and Packard. This was followed in 1917 by the V8 powered Model 8-88, known as the Silent Knight. While praised for its quiet operation, the sleeve-valve engine was complex and expensive to produce, even before paying Mr. Knight’s hefty royalty. In 1917. Willys-Overland sold over 133,000 cars, but only 2750 of these were the expensive Willys-Knights. By 1925, however, Willys would purchase Stearns, another luxury carmaker employing the Knight sleeve-valve design. Together, W-O’s luxury car sales had climbed to 50,000 and were extremely profitable.

1919 Willys Knight 8-88 (www.toledoblade.com)

Willys was also buying into the new and blossoming airplane industry. He purchased Curtis Aircraft Company and Duesenberg’s airplane engine operations. With America’s imminent entry into World War I, and the newest theater of war being the sky, this seemed a sound strategy. Willys ramped up production, not only for aircraft but also munitions.

Then, to the world’s great relief, but the dismay of John North Willys and others caught in the can-do spirit of patriotic capitalism, the Armistice came much more quickly than anticipated. Willys-Overland faced peace with an excess of both capacity and debt. The situation was made worse by an earlier move to relocate corporate headquarters from Toledo. By locating in New York City, JNW felt he would be closer to the action, facilitating control over his far-flung and growing empire. His mistake was that he underestimated his personal influence on the production workers in Toledo. Mr. Willys had been a very visible manager, putting in long hours and regularly seen jacketless on the factory floor. The workers respected him. They did not respect Clarence Earl, the man he put in charge of the Toledo operation. Earl was something of an autocrat and labor relations soured. An ugly strike ensued. The resulting rioting and bloodshed nearly forced the governor of Wisconsin to call out the National Guard. The plant had to be shut down for a number of months in 1919. Willys-Overland output dropped 26% in a year that American automobile production rose 48%.

Brushes with Bankruptcy

Just as Willys-Overland was struggling to right itself, a severe post-war recession struck. John North Willys found himself dangerously overextended. Investors and financiers lost faith in Willys. They approached Walter P. Chrysler to assume control of Willy-Overland. Mr. Chrysler had successfully turned around the fortunes at General Motor’s Buick division, but left the previous year when he became fed up with chairman Billy Durant’s constant interference. Chrysler reportedly didn’t want the W-O job, and so demanded an outrageous $1 million yearly salary on a 2-year contract. He thought the demand would be laughed at. Instead, it was signed immediately. A man of his word, Chrysler took the job.

walter P. Chrysler (www.allpar.com)

The relationship between Willys and Chrysler was tumultuous. This could be expected when two outsized personalities are forced together. From the start, Willys did not trust Chrysler’s motives. He was proved correct when the latter attempted to force out the former. But John North Willys, with that personal charm of a master salesman, persuaded shareholders to side with him. Chrysler moved on to run Maxwell-Chalmers, which he reorganized into the Chrysler Corporation. But not before he had renegotiated many overly optimistic contracts and divested all of Willys-Overland’s non-automotive businesses. Willys was back to profitability by the end of 1922.

Back at the helm and on a roll, JNW began to revamp his product line. He introduced the Willys Whippet in 1926, The Whippet was a thoroughly modern car based on European esthetics. It had a smallish 4-cylinder engine that still put out a healthy 35hp. This mill would be the basis for the 4-cylinder engines that would power Willys - and later Jeeps - for decades to come. Paired with a light body, the engine made the Whippet feel like a much more powerful car. Its spritely performance and good handling, combined with 4 wheel brakes - a first for a low priced car made the Whippet the new benchmark. Some even say that it was that excellence that finally convinced Henry Ford to replace his beloved but antiquated Model T.

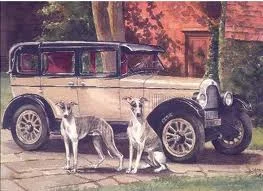

1927 Willys Whippet (advert Circa 1927)

The Whippet was a hit. By 1928 sales passed 300,000 and Willys bounded to third on the sales charts, behind only Ford and Chevrolet. It is noteworthy that while the Willys name is synonymous with the U.S. Army Jeep, the company actually sold more Whippets in the 1920s than Jeeps in the 1940s.

Success, however, was short-lived. The Whippet’s best year was 1928. That was when Ford shut down Model T production for four months in preparation for the all-new Model A. By 1929 Ford was back in business with the vastly improved car. Moreover, The Whippet’s low mass and its lusty motor made it a favorite for performance buffs. Whippets were regularly driven hard, and thus wore out quickly. They developed an ill-deserved reputation for brittleness. Nineteen twenty-nine saw Willys drop to 4th place in sales, and fell further to 6th in 1930. As the Depression sunk to its depths in 1931, Willys’ volume was a tenth of what it was 3 years prior.

Whether it was a sense that the good times could not last, or just pure luck, in the middle of 1929 John North Willys abruptly sold all of his common shares in Willys-Overland Company for a reported $25 million and resigned as president. Mr. Willys then accepted an appointment by President Herbert Hoover to be ambassador to Poland in 1930. In his absence, depressed conditions carried his former company toward bankruptcy. Willys-Overland lost $35 million from 1930 to 1932.

1933 Willys Model 77 (www.gasserplans.com)

JNW returned to his company to steer it out of receivership. Despite terrible business conditions and little money, by 1933, Willys was still able to develop and introduce its new Model 77. The 77 was an all-new design that furthered the Whippet ideal of a well-made, light weight car with excellent performance. This was also perhaps the first “streamlined” automobile in America. It had a sloping hood line, swept-back grill and integrated headlamps. The Chrysler Airflow of 1934 is usually cited as being America’s first mass-produced car to incorporate aerodynamic design principles. The Airflow did take streamlining to an extreme. But the Willys 77 may have been overlooked because it wasn’t really mass-produced. The few batches had to be done so with permission from the bankruptcy court. Only 6,500 Mobel 77s were built in its first year.

Mr. Willys’ tireless efforts to save his company were eventually successful, but he never saw the fruits of his labors. After a third of a century in the auto business, from its touch-and-go beginnings, through a meteoric rise, peppered with periodic and bloody shakeouts, John North Willys was there. As one of the pioneers, he might not have liked where the industry was headed, dominated by a few large players, as the great Independents one by one fell aside. He was spared that particular indignity but not the ultimate one. In the summer of 1935 John North Willys died at his home in Bronxville, NY of a massive heart attack.

Resurrection

Ward Canaday

While men have but one life, companies can have many. Willys-Overland was almost cat-like in this respect. Soon after Mr. Willys’ death, a group of investors, led by long time sales executive Ward Canaday, was able to secure management control over the company and have its debts wiped away. Amongst his early moves at the helm, Canaday brought in three men who would lay the company’s foundation for the next dozen years.

The first was an innovative free-lance designer named Amos Northrop. Northrop had been design chief for Willys in the late 1920s where he penned the beautiful Willys-Knight Model 66 Roadster. He left to do the progressively more stunning 1931 REO Royale and 1932 Graham Blue Streak. Now back at Willys, Northrop took a bold approach on a shoestring budget. He widened the frame of the old Model 77 and gave it swept back fenders and a bold, thrusting nose. The result was the Willys Model 37. Northrop is perhaps best known for his “Shark Nose” Grahams. Comparing the two side by side suggests the Willys may have been an early “sketch pad” for the more radical car.

1937 Willys Model 37 (www.wokr.org)

Joseph W. Frazer was hired to bring the Willys 37 to market. Previously Frazer had been a top sales executive at Chrysler Corporation, where in the late twenties he guided both the Plymouth and DeSoto brands into existence. The low-priced, well-engineered Plymouth arguably kept its parent afloat through the turbulent depression years. Frazer positioned the new Willys as a practical alternative to Detroit’s “colossuses.” The 37 got up to 35mpg and was advertised as using “Half the gas…twice the smartness.”

Willys’ sales quadrupled to more than 51,000 that year. Profits swelled to $500,000. Willys’ sales were still a fraction of Whippet’s heyday, but things were looking brighter as the Great Depression finally began to loosen its grip on the nation.

"go-devil" engine (www.allpar.com)

The third pillar of Canaday’s efforts was coxing an engineer over from Studebaker named Barney Roos. Roos had designed the legendary 9-bearing strait-eight engine that powered the magnificent Studebaker Presidents. In the decade or so since Willys’ tried-and-true 4-cylinder engine debuted in the Whippet, it had acquired and additional 13hp, now up to 48. Impressive, but enough if the Model 37 was going to succeed as a viable alternative to Detroit’s ever more powerful machines. Roos took the little 4-banger and upped the compression, added a better carburetor and camshaft, maybe even said a few magical incantations. Output was boosted all the way up to 60hp. The new engine was said to “Go like the Devil,” which gave it its name. The Go-Devil Four would power Willys’ products for two more decades, including the Jeep.

Willys Americar (Willys advert circa 1941)

The Go-Devil Four first made its debut in the updated 1941 Willys Americar. The Americar’s shape was even more slippery than the Model 37 on which it was based. With 20% more horsepower now on tap, it was also faster.

And the Americar would go faster still. Its wind-cheating shape and low mass, combined with a spacious engine bay, made it a favorite starting point for drag racers, who swapped in flathead Ford V8s to make Americars really go like the Devil. Willys were legendary during Southern California’s “Gasser Wars” of the early 1950s.

Willys Gassers by bruce kaiser (www.kaiserCarArt.com)

Despite the efforts of Canaday and his team, many customers were still wary of Willys’ multiple flirtations with extinction. Of all the major U.S. car manufactures in 1941, Willys ranked ahead of only Lincoln. Nevertheless, sales were sufficient to keep the doors open until new military contracts could be signed. Then, after the war, a new Willys savior would arrive home from the front.

The U.S Army Jeep

US Army jeep in wwii by kim wang (www.fineartsAmerica.com)

What is Jeep doing in a story about a make that didn’t make it? It is one of the most successful and valuable brands in the world. At its core though, the Jeep is a bit like the soldiers it transported. It did the grunt work and served its commanders. Willys, Kaiser, AMC, Renault in America, and Chrysler, one by one over the years those commanders would retire or be absorbed, while the Jeep soldiered on. It is Willys that usually gets the credit for fathering Jeep. Indeed, Willys built more than a third of a million of them over the course of WWII. It was Willys president, Joseph W. Frazer who ordered in 1943 that a patent be registered on that not yet storied name. But it was a small firm in Butler PA who was first to produce the nimble light reconnaissance truck that would soon be called a Jeep.

Volkswagen Type 82 Kubelwagen (www.kfzderwehrmacht.de)

In the spring of 1940, war was raging across Europe. In one of a multitude of preparations for a response, the U.S. Army studied the effectiveness of the German light reconnaissance car called the Volkswagen Type 82 Kubelwagen, and its role in the wehrmacht’s blitzkrieg across France. Within weeks of Paris’ fall, the Army knew what it wanted.

Requirements for an American light reconnaissance vehicle were formalized and put out for bid on July 11, 1940. Even though this would be a lucrative contract, the Army’s crushing 7-week timetable for a delivered prototype meant that of the 135 companies contacted, only two bid on the job. Willys Overland was one of these, but they could not get a finished demonstrator to the Army before the deadline. The other firm, American Bantam, did deliver on time what would in a few years become the world’s most recognizable vehicle.

But as any experienced soldier knows, winning the battle doesn’t always win you the war.

A decade earlier, The American Austin Company began building a licensed version of Britain’s immensely popular Austin Seven. The company’s Butler, PA plant turned out 20,000 of the tiny cars over five years before they ran into difficulties and went bankrupt. A local entrepreneur named Roy Evans bought the firm out of receivership in 1936 and renamed it American Bantam. Evans immediately had the little Austin extensively redesigned in the hopes of making it more appealing to American tastes. The results were a lovely roadster, along with a woody wagon and a delivery van. These little cars were indeed appealing, but they were just too small. Only 7,500 more Bantams were sold through 1940. The company was again teetering on the edge when the Army’s call for bids went out.

To win the bid that could save his company, Evans approached the talented freelance engineer, Karl Probst, to build Bantam’s prototype. Probst initially refused the offer from the cash strapped company, which was in the form of a consignment fee in place of salary. Some accounts say Probst’s old friend William Knudsen, former president of General Motors and recently appointed head of the government’s new War Production Authority, persuaded Probst to accept the offer. Others report that he was moved to patriotism by Winston Churchill’s, “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight in the streets” speech during the Battle of Britain. Whatever the reason, Probst took the job. He was able to deliver blueprints to Bantam in just 5 days.

American Bantam 40BRC "Blitz buggy" (www.allpar.com)

It took another 44 days of round-the-clock work to build the vehicle. Using off-the-shelf parts from a variety of suppliers, Bantam was able to finish a prototype literally hours before it was due at the Army proving grounds in Camp Holabird, Maryland. There was no time for a proper break in on the machine, which they nicknamed the Blitz Buggy. Bantam’s engineers used the 170-mile drive from Butler to the to do the job. The vehicle was called the 40BRC (Bantam Reconnaissance Car) and it was the only prototype delivered within the army’s timeframe. Bantam won a contract to supply 70 more BRCs for further evaluation.

Three months later, Japanese navy bombers attacked at Pearl Harbor. Soon after that, American Bantam would become an early casualty of the war.

As mentioned earlier, the other company to bid on the contract was Willys-Overland, but they did not get a vehicle to Camp Holabird in time for initial consideration. Willys did however manage to get a couple of their engineers there in order to “help” evaluate the BRC. The Army soon recognized that the production facilities of the struggling American Bantam would be nowhere near adequate to meet their demands. They re-opened bidding.

Willys-Overland was asked to produce additional prototypes. The 40BRC blueprints, now government property, were handed over to Willys. Joseph Frazer put Barney Roos, on the project, who again worked his magic. Even though his vehicle was a bit heavier than the army’s specifications, the punch of the 60hp Go-Devil engine won them over.

Willys MA 1/4 ton lrv (source unknown)

But even Willys-Overland could not fully supply the Army’s needs. The contract was further extended to the Ford Motor Company. Each company was encouraged to make improvements on the original design. The result was the Model MA Army reconnaissance car, later to be known as the Jeep.

Jeeps shipping out (www.jeepcollection.com)

By the cessation of hostilities in 1945, nearly 650,000 Jeeps were built. Willys-Overland built 362,000 of them, while Ford made another 281,000. American Bantam produced only 2675 40BRCs. Because of modifications made early on to the design, the Bantam version was deemed by the army to be non-standard and therefore unusable. All remaining 40BRC were shipped to Britain and Russia as part of the Lend-Lease program.

Of all the makers who take credit for Jeep’s lineage, the tenure with American Bantam was the briefest by far. Bantam created the first of what would become one of the most iconic vehicles of all time, and it barely receives a footnote for its efforts. Even if they could have imagined the ultimate demand, the little company from Butler never could have met it. Truth is, like a wayward father who meant well, American Bantam was unfit to raise the Jeep. War is hell.

America’s Soldier; Willys’ Savior

Peace dealt Willys-Overland a difficult hand. By the time World War II finally reached its conclusion, four years of pent up automotive demand was screaming to be freed. Carmakers were in a mad scramble to ramp up civilian production and sell every car they could build. It was a seller’s market, one that extended beyond just the manufacturers. Suppliers of everything from components to steel could pick and choose the highest volume contracts with the fattest profits. After a terrific run with the military Jeep, CEO Ward Canaday now wanted badly to put on his civvies back on and start building cars again. But no supplier wanted to produce bodies for a small maker like Willys Overland, especially one with a couple of bankruptcies under its belt. Frozen out, Willys was forced into the role of scavenger, looking for automotive opportunities wherever they could be found. What better vehicle was there for probing at the fringes than the go-anywhere Jeep?

Jeep CJ2A (Willys advert circa 1946)

The only “car” Willys could produce at the end of the war was the CJ2A, a civilian version of the military Jeep. Joseph Frazer had left Willys Overland before the end of the war to partner on a new automotive venture with Henry J. Kaiser. But not before he had the foresight to secure for Willys a patent on the Jeep brand name. It wasn’t exactly what Canaday wanted, but it would have to do. The Jeep brand was born.

Charles Sorensen was brought in to replace Frazer. Known as “Cast Iron Charlie,” from his early days at the Ford Motor Company, Sorensen was the man responsible for Ford’s implementation of the modern automobile assembly line. That hadn’t stopped an increasingly senile Henry Ford form abruptly fired his old friend. Now at Willys, Sorensen set about finding any means possible to expand the appeal of the Jeep. He soon found a body maker willing to supply Willys-Overland. The only catch was that the bodies would be coming from a plant built for stamping sheet metal for household appliances. Turning refrigerators into cars would require a bit of genius. Fortunately, Brooks Stevens was available.

Brooks Stevens (www.IndustrialDesignSocietyofAmerica.org)

1947 Jeep Station Wagon (www.LostJeeps.com)

Stevens was a young industrial designer whose genius was turning useful things into useful things that were elegant. The directive Sorensen gave him was to take what amounted to a little army truck with a washing machine body bolted onto its ass, and make it appealing. What Brooks Stevens created was an entirely new category of vehicle that was 40 years ahead of its time. The 1946 Jeep Station Wagon was a 6-passenger car built on a light truck frame. Today, a vehicle possessing those qualities would be called an SUV. In the late forties most people just called it strange.

There were a few trailblazers who appreciated the versatility the new Jeep offered. It was sturdy, economical and could go most anywhere. The Jeep was also the first all steel bodied wagon in America. After an abbreviated 1946 production run, Willys sold over 33,000 in 1947 - 50% higher than the pre-war Americar. They made an average of 30,000 Jeep Station Wagons a year from 1947-51.

Despite the Station Wagon's success, Willys CEO Ward Canady still wanted to build a proper car. The market for cars was red hot and Canady wanted Willys in the middle of it. Charlie Sorensen, the seasoned production man, saw the direction that the post-war auto industry was headed. He knew it would be several years before body capacity freed up to the point where Willys could make cars. Even if he could do so, Sorensen was not sure the wisdom of trying. Independent makers attempting to compete with the Big 3’s economies of scale didn’t stand a chance. He liked the idea of having a much smaller market all to himself. He wanted Willys to focus on Jeeps, lowering costs and making evolutionary improvements. He was content to leave the cut-throat car business to others.

Two strong personalities clashed, and the one who owned the company won. Less than a year after the Station Wagon’s debut, Willys had a new president. That was James Mooney, a former GM man who immediately set about planning for a lightweight compact car that sounded very much like a modern Americar or Whippet. And he ran into exactly the obstacles Sorensen had foreseen. The post-war car boom was still going strong, and Willys continued to be stymied in its quest for suppliers.

1948 Jeepster (www.JeepsterJim.com)

In 1948, however, they got a little closer. The resourceful Brooks Stevens was again given a mandate - but few resources - to build a new kind of Jeep-based car. This time it was, as the press releases touted, a “sports-type” vehicle that was “unique and stylish,” if not exactly beautiful. It is “…a sports phaeton whose low and racy appearance reflects the continental concept.” Perhaps that meant that that the Jeepster reminds us a little of an oversized MG-TC. At any rate, the new Jeepster was meant to attract young people who wanted something sportier than a traditional convertible. It had white-wall tires, a chrome grill, and overdrive as standard equipment. Nineteen thousand Jeepsters were built from 1948-51.

1949 Jeep 4WD Station Wagon (www.Allpar.com)

In 1949, 4-wheel drive became available on the station wagon. A new “Lightning” F-head 6-cylinder engine was offered as an option on both two and 4-wheel drive models. In 1951, the venerable Go-Devil four was retired after a quarter century of service. It was replaced by a new, more powerful mill dubbed the “Hurricane Four.”

Aero through the Heart

By the end of 1950, the supplier situation had stabilized to a point where Willys-Overland could resume traditional automobile production. Clyde Paton, a noted Packard engineer now gone freelance, had developed a new lightweight car with an advanced unit-body design. Paton pitched his design to W-O. where it was enthusiastically accepted. Within 18 months Willys had its first real automobile in 10 years. The 1952 Aero-Willys had the makings of a winner.

Like most of the Independents, Willys-Overland’s survival strategy in the early 1950s focused on niche markets otherwise overlooked by the Big Three. While Jeep had the light utility market all to itself, its growth prospects at that time were limited. Smaller cars seemed to offer a much larger volume source. For years, the basic cars from Ford, Plymouth and Chevrolet had been getting bigger and heavier. This was opening up a whole new segment of the market called compacts. All the major independents were now speeding to fill the void. Nash introduced its Rambler in 1950, the Kaiser Henry J bowed in 1951, and the Hudson Jet followed in 1953.

1950 Nash Rambler

1951 Kaiser Henry J

1952 Aero-Willys

1953 Hudson Jet

The Rambler was a cool little car but its styling was polarizing. The Henry J looked a bit strange as well, and it wore its cheapness on its sleeve. The Jet was a good performer, but its top-heavy proportions made it gawky and graceless. The Aero was easily the best looking of the bunch. Styling came from the pen of Phil Wright, who gave the Aero a clean look with fine proportions and just a spring bud of a pair of tailfins. It had a unit-body design that allowed more interior room, less weight and a better ride. Combined with Willys’ new “Lightning” six-cylinder engine that put out a class best 90hp, made Aero a superior performer as well. In fact, with the 1952 Aero weighing in at just 2700lb, it had the best power to weight ratio of any car in America that year. Ward Canaday called it “…the nearest thing to flying you’ll find on the highway."

Aero-Willys Falcon (www.American-Automobiles.com)

Had the Aero been a Ford or a Chevy or a Plymouth, many hundreds of thousands would have been sold annually. It was that good a car. But tiny Willys-Overland did not have the economies of scale to be able to price the car competitively. The smaller, lighter Aero cost about 10% more than the full-sized price leaders from Ford, Chevy or Plymouth. A smaller car that is a cut above the rest would be a selling point today, but in 1950s America bigger was considered better, even if it wasn’t. Willys managed to sell 90,000 Aeros in its first two years on the market. Not bad but not enough.

Merger with Kaiser

Kaiser-Frazer Motors had been founded toward the end of WWII by famed industrialist Henry J. Kaiser and former Willys president, Joseph Frazer. They had high hopes of taking on the American automotive status quo. The Kaiser and Frazer brands were the first all-new cars to appear after the war and initial sales were strong. But at the turn of the decade, as supply and demand found their equilibrium, K-F struggled to compete. The two founders clashed over strategy. Frazer resigned. The source of their dispute, the utilitarian compact Henry J unveiled in 1951, failed to meet sales expectations. That same year, the reengineered larger Kaisers were beautiful, well designed cars, but they too were floundering in the marketplace. Consumers were beginning to lose faith in the viability of the independent makes.

Kaiser industries advert circa 1953

Henry J. Kaiser was not used to failure. He had built an empire carving civilization out of the wilderness. The Willys lineup of all-purpose Jeeps that had no competitors, plus a compact car that was superior in almost every way to his namesake small car. By purchasing Willys-Overland, Kaiser could at least partially save face in the auto industry. The $60 million deal went through in April 1953.

The Kaiser-Willys tie up kicked off a wave of consolidation among the Indies, one that would prove to be too little too late. The following year Ford and Chevrolet embarked on a slash and burn sales war that pushed down car prices and laid waste to the independent makers. Hudson was absorbed by Nash. Packard rushed into a disastrous merger with Studebaker. Before the close of 1955, Kaiser Industries simply pulled the plug on U.S. automobile production, after selling just 15,000 more Aeros in its final 2 years.

Jeep CJ5 (www.bringatrailer.com)

Jeep soldiered on as a division of Kaiser. Improvements continued to be made. A redesigned Jeep CJ-5 was introduced in 1954. The last vehicle to be developed under Willys-Overland leadership, the CJ-5 was 3 inches wider, 1 inch longer than its predecessor, and had a stronger frame and a better ride. The CJ-5 would spawn many derivatives and consistent profits over its 29 years in production.

Kaiser Industries dropped the Willys name in 1963, becoming Kaiser-Jeep. After 61 years, the storied American brand was no more.

The Beat Goes On

While it was unable to compete in the US marketplace, the Aero was destined to have fun in the sun. Its modern, compact design, good looks, sturdy construction and stellar performance made it an ideal car for a newly industrializing country with no automobile industry of its own to make a splash. The Aero’s tooling eventually found its way to Brazil in 1958. A new Kaiser subsidiary called Willys do Brasil began production of a mildly face lifted Aero in 1960.

Willys do brazil Aero (www.Hoonverse.com)

willys do brazil Rural (willys advert circa 1966)

Willys do Brazil sought to give their car a more unique identity. For that they hired Brooks Stevens to once again work his design magic on the Willys line. He gave the Aero a modern new body to create the handsome Itamaraty 2600. The Itamaraty came to be the symbol of a Brazilian automobile.

Willys itamaraty 2600 (Willys advert circa 1964)

In 1967, Kaiser sold its Brazilian and Argentine operations to the Ford Motor Company, but production of the popular Aero-based cars continued well into the 70s. Willys do Brasil, and later Ford, would sell over 117,000Aeros, Itamaratys and other derivatives from 1960-1974. During its 20 years in production, under 3 owners and on two continents, nearly 220,000 Aeros were produced.

All told, Willys-Overland built nearly 2.5 million cars during its half century as an independent company. Add another half a million Jeeps made between 1941 and 1954, and it’s not a bad showing for a make that didn’t make it.

Copyright@2017 by Mal Pearson

Sources and Further Reading

The Old Milford Press www.oldemilfordpress.com

Willys Overland Knight Registry www.wokr.org

The Jeep Story by Patrick Foster Krause Publications (2004) www.oldemilfordpress.com

John North Willys, Automotive Pioneer by Curtis Redgap www.Allpar.com

History of Early American Automobile Industry: 1891-1929: Overland www.EarlyAmericanAutomobiles.com

The American Bantam Story: Parts 1-4by Robert D. Cunningham www.theoldmotor.com

Willys-Overland 1945-1955 by Patrick Foster Hemmings Classic Car November 2012 www.hemmings.com

Willys' Long Farewell by Patrick Foster Hemmings Classic Car January 2008 www.hemmings.com

Willys 37, Basic Transportation in Style by Arch Brown Special Interest Auto #156, Nov/Dec 1996

The Aero Mystery by Patrick Foster Hemmings Classic Car June 2017 www.hemmings.com

The Other Willys by Jim Allen Autoweek December 10, 2012 www.Autoweek.com

The Incredible Jeep by Ronald H. Bailey www.Historynet.com