The boom times of the late nineteen-forties wasn’t just about supply and demand. Engineers were beginning to look at old assumptions with new eyes. Before the war, the American automobile industry had pretty much settled on a basic design blueprint. Cars were laid out as a rectangle, with a wheel at each corner. The rear axle drove the car while the front one steered it. The engine was mounted longitudaly in front, with the passengers seated behind. This layout proved simple, effective and cheap to build. It became the industry standard. Now suddenly, all bets were off. Daring engineers who had helped win a world war itched to test the norms of conventional design. They began to think outside that rectangular box of design tyranny.

Geometry was the first edict to be challenged. Because the rectangular wheel pattern was widely accepted as the most stable layout for an automobile, varying from that norm required some significant advantage in order to be embraced by the marketplace. The Davis Divan used a triangle layout with a single wheel in front. The benefits were notable; reduced weight, improved aerodynamics, and better low speed maneuverability. But all the improvements in the world don’t matter if the car isn’t stable, and cornering at speed in a 3-wheeled car can be a very de-stabilizing experience.

Reliant Robin (www.dailyKos.com)

Moving along in our geometry studies: Shortening from rectangle to square makes for a very choppy ride with no compensatory benefits - and as far as we know, no one has ever tried to make a circular car. But there would be one entrepreneur during the 1940s who would give the rhomboid a shot.

In the early days of the automobile, the rhomboid - or diamond wheel pattern - was considered, but soon dismissed. Riding on three tracks was not very practical on the two-track roads that more than a century ago made up quite a lot of the country’s transportation system.

1907 Vandegrift Autocycle (RomboidCars Facebook page)

By the 1930s, the quality of roads had improved dramatically. A decade prior, it didn’t matter much if a car could hit 60 or 100 mph because there were few roads you could do more than 40 without your car being shaken to bits. Now, the speeds that modern roads could accommodate exposed the aerodynamic limitations of the traditional brick-shaped car. To go faster, carmakers had to make a choice: They could build their cars with bigger, more costly engines to power them though wind resistance, or they could make their cars more streamlined, to slice through the air more efficiently, allowing them to use existing engines.

One of the earliest pioneers in automotive aerodynamics was Gabriel Voisin. He was a brilliant French aeronautical engineer who’s early century aircraft designs formed the foundation his nation’s first air force. But during WWI, Voisin was said to have been horrified by the death and suffering caused by his creations. After the armistice, he quit aviation, and addressed his expertise in physics and streamlining to the automobile.

Voisins at the Mullin Museum in Oxnard (Mal Pearson)

Voisin honed the shape of his cars to cheat the wind and hug the road. By 1938, he had gotten to the point where he recognized that a diamond wheel layout might allow him to shape a car more like a projectile that shoots through the air. He had taken what he called “middle-wheel drive” to the prototype stage with the Losange Voiture de l’Avenir (lozenge car of the future). With its aerodynamic shape, and 7-cylinder sleeve-valve radial aircraft engine, le Losange was the most complete coupling to date of the airplane and the automobile. Before Voisin could address the considerable problem of just how to get this car over a service pit, France was invaded and the project had to be abandoned.

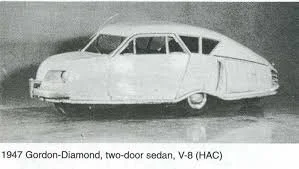

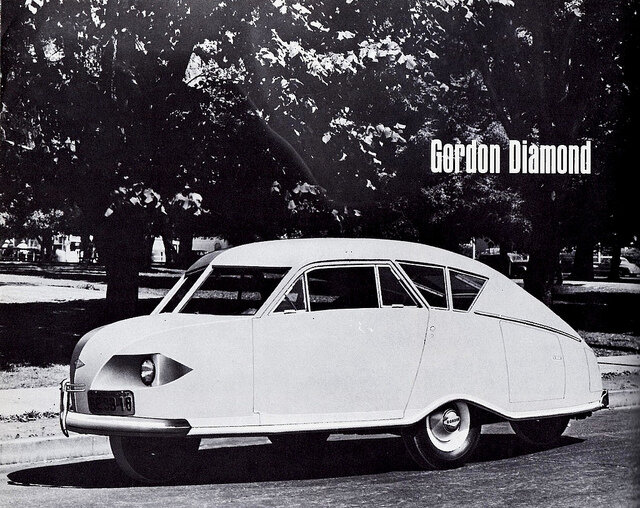

Soon after the war, an American engineer named H. Gordon Hansen from San Lorenzo, California – which was just across the bay from the Silicon Valley – read in an engineering journal about Voisin’s lozenge-shaped car and got an idea. At the time, Hansen wasn’t thinking so much about aerodynamics but of safety. He envisioned the ideal safety car as having wrap-around bumpers in order to better fend off collisions. This would require a kind of football shaped body. But such a car on a conventional floorplan would be far too wide and bulky to be practical. He briefly considered a 3-wheeler like the Davis, but dismissed it as too unstable. After seeing the Losange, he settled on a diamond pattern for the chassis. As such, his car was called the Gordon-Diamond.

We don’t know why Mr. Hanson chose his middle name as a moniker for the car, instead of his last which is traditional. Perhaps it sounded better. Or maybe he was a conservative guy, wanting to put a bit of distance between himself and this radical machine. But the reason doesn’t really matter. Almost nothing about this car could be considered traditional.

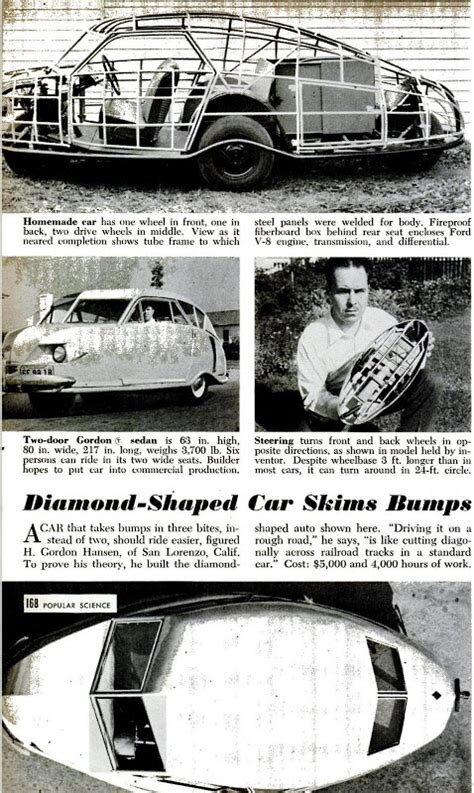

The 1948 Gordon-Diamond was about the same length and weight as a contemporary Ford. It used a Ford flathead V8 engine, so acceleration was similar. And they both had four wheels. The comparison ends there. The Diamond is laid out with its drive wheels running through a center axle. Single wheels fore and aft work synchronously to steer the car. The driver and passengers sit between the front wheel and the center axle, while the engine is mounted behind. All of this sits within a tubular steel, unit-body frame.

This setup had its advantages. With the front and rear wheels steering and the center axle propelling, the Diamond had a 70% shorter turning radius than a traditional car. The independently suspended front and rear wheels also provided stability for the solid center axle as it hits a bump, making for a smoother ride. It also moved through the air more efficiently, offering an improvement in top speed and fuel economy.

The Diamond’s only drawback was with its geometry… or rather, the physics put in motion by the Diamond’s particular geometry. With its driving wheels stable at the center, and single front and rear wheels steering in different directions, the car had a tendency to want to turn itself into a top and go spinning off. This was especially true in strong cross winds, or when the roads got slick…or God forbid both! In fact, the Diamond’s handling traits were such that it was quite miraculous that Mr. Hansen’s theories about wraparound bumpers and the mitigation of impact were never put to the test.

Hansen was said to have had discussions with established carmakers, with first Kaiser-Frazer and then Packard, about licensing the Diamond design. These went nowhere. The car’s strengths were not enough to get past its challenging driving dynamics. By 1949, the Diamond dream was dead.

In the end, Gordon Hansen built just the one car. In 20 years driving it around Northern California, he piled up nearly 100,000 miles. He must not have minded crowds. In 1967, Hansen agreed to sell the Diamond to Bill Harrah for his collection based in Reno, NV. After Harrah’s death, it was sold off to a private collector in Montana, where at last report it still resides.

Copyright@2020 by Mal Pearson