Willys Part 1: Before the Jeep

/Willys Overland is best known as maker of the original Jeep. With good reason. That little truck helped win a world war. The parent company, however, predated its famous aspiring by 40 years, holding a memorable place in its own right in the annals of automobile history. The original Overland of 1902 was one of the very first cars to employ the front engine, rear drive layout that would become the industry standard for the next half century. Willys was the second bestselling car in America during the 1910s, still #3 by the late 1920s, and its strong performing compact cars of the 1930s dominated that category decades before anyone thought to give it a name. The Willys brand did not survive the industry’s post-war consolidation. But through the Jeep name, passing though no fewer that 7 owners...and counting, the Willys-Overland soul lives on.

The Overland

Willys-Overland was born in the infancy of the American automobile industry. The Olds Curved Dash had just burst onto the scene. Its tremendous acceptance by the general public convinced many an industrial visionary that there was a bright future in the automobile. Two of these of these were Charles Minsall and Claude Cox. The former was managing director of the Standard Wheel Company of Cleveland, OH. Minsall smelled big profits in automobiles, even though he knew nothing about the contraptions himself. Cox was a young engineer who had built his first motorcar as a senior thesis at the Ross Polytechnic Institute. Minsall had heard good things about Claude Cox and hired him to design and built a car for the newly created automotive division of Standard Wheel.

Overland Runabout (www.rmauctions.com)

It was called the Overland, a runabout like the Olds Curved Dash. Unlike the Olds, and most other early cars, the Overland’s 2-cylinder water-cooled engine was mounted up front rather than under the seat. This configuration would soon become the industry norm. Unfortunately, the Overland’s engineering excellence did not extend to Standard Wheel’s ability to manufacture and sell it. Just eighty-two Overlands were built in 1903-05, none of them at a profit. Minsall decided he had had enough of the red ink. Just as Cox was readying to produce a larger 4-cylinder model, he was informed that Standard Wheel was no longer interested in making cars. Had the Overland story ended here it would not have been an uncommon experience. During the first dozen years of the industry, hundreds if not thousands of startup carmakers passed into the annals of obscure history books.

But the Overland story did not end here. A successful carriage maker named D.M. Parry was a major customer of Standard Wheel. Wanting to get into the automobile business himself, and admiring Claude Cox’s work, Parry stepped in to save the day…almost. In exchange for 51% of the new Overland Auto Company, Parry would finance a resumption of operations at a plant in Indianapolis. Production was about to begin when the Panic of 1907 swept the nation. It washed away much of Parry’s fortune, leaving Overland Auto high and dry. Claude Cox found himself with a partially built factory, a pile of parts, several hundred workers, and no money to pay for any of it.

The days looked dark for Overland, but another savior would soon appear.

John North Willys

John North Willys was raised in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York. John was a salesman and an entrepreneur from an early age. He opened a laundry business in 1888 at the age of 15 and sold it a year later for a thousand-dollar profit. His father urged Willys to use this windfall to study law, a field in which he had no particular interest. Upon his father’s death a few years later, Willys quit the law and in 1892 he became a bicycle distributor in his hometown of Canandaigua, NY. Four years later he had expanded to Elmira. Soon he was selling out the entire production of several bicycle factories. By 1900 his businesses had annual revenue of half a million dollars.

Willys saw his first automobile on a business trip to Cleveland, OH in 1899. He noted the intensity in which crowds viewed this new machine. An astute observer of business trends, Willys concluded that the automobile would one day replace the horse - as well as the bicycles he was now making - as America’s first choice in personal transportation. Within a year he had become a dealer for the Pierce automobile. He managed to sell 2 cars. Undaunted, he took on a franchise for the new Rambler, built by The Jeffrey Co. of Kenosha, Wisconsin. Willys sold 8 cars in 1902. When riding a wave of the future, to achieve success one must be both opportunistic and patient. John North Willys was both. He sold 20 cars in 1903.

John North Willys (www.AllPar.com)

Americans were becoming steadily more aware of the automobile. The excitement and freedom car ownership offered was beginning to erode their skepticism. By 1906 Willys was casting about for expanded opportunities. He wanted more than just a new car to sell, but rather one good carmaker for which he could become sole distributor. In the Overland Motor Company of Indianapolis, he thought he had found what he was looking for. Willys paid $10,000 as down payment on a contract for 500 cars – what was to be Overland’s full production run. After many weeks waiting for his cars and a number of unanswered telegrams and telephone calls, Willys was getting anxious. He boarded a train for Indianapolis to find out what had happened to both his order and his money. Upon his arrival at the Overland factory, he found no activity, a few partially-built cars, and one distraught Claude Cox, just recently stripped of his financial backing. Most men would have walked away from the mess and written off their loss. Most men did not have John North Willys’ optimism and drive.

Using his skills of persuasion, Willys first convinced the firm’s creditors to put him in charge of the operation. He then set out to recapitalize the company. He talked suppliers into granting him 90-day terms as he reorganized the factory. Mr. Willys wasn’t afraid to roll up his sleeves and get his hands dirty. The factory workers respected him for that. It didn’t hurt that he also made sure all of them who stayed on received back pay plus a loyalty bonus. Willys was able to revive Overland’s production and sell 46 cars in 1907. Then he sold 465 in 1908. Overland Motors was reformed as the Willys-Overland Company and earned a $50,000 profit that year.

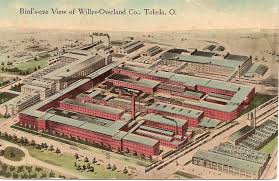

The new company’s soon found itself constrained by production limitations. So much so that a circus tent had to be set up nearby to house a makeshift expansion. Thus, when a factory in Ohio came up for sale the following year, Willys jumped at the opportunity. All production was moved to Toledo, where descendants of Willys-Overland’s products are still built today.

Some of Mr. Willys’ actions, especially the move to Toledo, did not sit well with his chief engineer, Claude Cox, who resigned in anger. Willys, however, owned the company, which owned all the patents, making Cox expendable.

The first Toledo-built Willys-Overland debuted in 1910. It was called the Model 38. Nearly 16,000 of them were sold that year. By 1912, sales had doubled to 32,000, making the Overland was the #2 selling car in America. The Model 38 used a sliding gear transmission pioneered by Packard making it simpler to drive than the #1 selling Ford Model T with its planetary box. The Overland was more expensive than the T, but it also enjoyed a better reputation for quality. By 1916, Willys’ sales surpassed 142,000, which was good for nearly 10% of the 1.5 million cars sold that year.

Willys-Overland Model 38 (www.AllPar.com)

Willys-Overland Expands

During the next decade, John North Willys went on a buying spree, greatly expanding his business empire. He bought Gramm Motor Trucks, which in 1913 would begin producing the first vehicle to carry the Willys name. Soon after Willys entered the premium car market. On an ocean journey to England, Willys met an engineer names Charles Knight. Knight had developed a new valve design that was far smoother than traditional engines. They talked extensively about the benefits of what Knight called his “sleeve valve,” which allowed for a much smoother operation by replacing the traditional and rough running poppet valves with precision sleeves to control intake and exhaust.

Knights Sleeve-Valve engine (www.Wikipedia.com)

Upon reaching England, Willys hired a car equipped with Knight’s sleeve valve engine and proceeded to log 4,000 miles over the island’s primitive road system. He returned to America impressed and motivated. He commissioned a new luxury car called the Willys-Knight in 1914, a fine car that would compete with the likes of Cadillac and Packard. This was followed in 1917 by the V8 powered Model 8-88, known as the Silent Knight. While praised for its quiet operation, the sleeve-valve engine was complex and expensive to produce, even before paying Mr. Knight’s hefty royalty. In 1917. Willys-Overland sold over 133,000 cars, but only 2750 of these were the expensive Willys-Knights. By 1925, however, Willys would purchase Stearns, another luxury carmaker employing the Knight sleeve-valve design. Together, W-O’s luxury car sales had climbed to 50,000 and were extremely profitable.

Willys-Knight 8-88 Silent Knight (www.toledoblade.com)

Willys was also buying into the new and blossoming airplane industry. He purchased Curtis Aircraft Company and Duesenberg’s airplane engine operations. With America’s imminent entry into World War I, and the newest theater of war being the sky, this seemed a sound strategy. Willys ramped up production, not only for aircraft but also munitions.

Then, to the world’s great relief, but the dismay of John North Willys and others caught in the can-do spirit of patriotic capitalism, the Armistice came much more quickly than anticipated. Willys-Overland faced peace with an excess of both capacity and debt. The situation was made worse by an earlier move to relocate corporate headquarters from Toledo. By locating in New York City, JNW felt he would be closer to the action, facilitating control over his far-flung and growing empire. His mistake was that he underestimated his personal influence on the production workers in Toledo. Mr. Willys had been a very visible manager, putting in long hours and regularly seen jacketless on the factory floor. The workers respected him. They did not respect Clarence Earl, the man he put in charge of the Toledo operation. Earl was something of an autocrat and labor relations soured. An ugly strike ensued. The resulting rioting and bloodshed nearly forced the governor of Wisconsin to call out the National Guard. The plant had to be shut down for a number of months in 1919. Willys-Overland output dropped 26% in a year that American automobile production rose 48%.

Brushes with Bankruptcy

Just as Willys-Overland was struggling to right itself, a severe post-war recession struck. John North Willys found himself dangerously overextended. Investors and financiers lost faith in Willys. They approached Walter P. Chrysler to assume control of Willy-Overland. Mr. Chrysler had successfully turned around the fortunes at General Motor’s Buick division, but left the previous year when he became fed up with chairman Billy Durant’s constant interference. Chrysler reportedly didn’t want the W-O job, and so demanded an outrageous $1 million yearly salary on a 2-year contract. He thought the demand would be laughed at. Instead, it was signed immediately. A man of his word, Chrysler took the job.

Walter P. Chrysler (www.AllPar.com)

The relationship between Willys and Chrysler was tumultuous. This could be expected when two outsized personalities are forced together. From the start, Willys did not trust Chrysler’s motives. He was proved correct when the latter attempted to force out the former. But John North Willys, with that personal charm of a master salesman, persuaded shareholders to side with him. Chrysler moved on to run Maxwell-Chalmers, which he reorganized into the Chrysler Corporation. But not before he had renegotiated many overly optimistic contracts and divested all of Willys-Overland’s non-automotive businesses. Willys was back to profitability by the end of 1922.

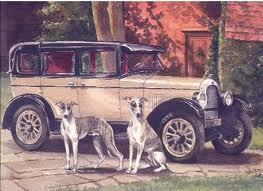

Back at the helm and on a roll, JNW began to revamp his product line. He introduced the Willys Whippet in 1926, The Whippet was a thoroughly modern car based on European esthetics. It had a smallish 4-cylinder engine that still put out a healthy 35hp. This mill would be the basis for the 4-cylinder engines that would power Willys - and later Jeeps - for decades to come. Paired with a light body, the engine made the Whippet feel like a much more powerful car. Its spritely performance and good handling, combined with 4 wheel brakes - a first for a low priced car made the Whippet the new benchmark. Some even say that it was that excellence that finally convinced Henry Ford to replace his beloved but antiquated Model T.

Willys Whippet (advert CIRCA 1927)

The Whippet was a hit. By 1928 sales passed 300,000 and Willys bounded to third on the sales charts, behind only Ford and Chevrolet. It is noteworthy that while the Willys name is synonymous with the U.S. Army Jeep, the company actually sold more Whippets in the 1920s than Jeeps in the 1940s.

Success, however, was short-lived. The Whippet’s best year was 1928. That was when Ford shut down Model T production for four months in preparation for the all-new Model A. By 1929 Ford was back in business with the vastly improved car. Moreover, The Whippet’s low mass and its lusty motor made it a favorite for performance buffs. Whippets were regularly driven hard, and thus wore out quickly. They developed an ill-deserved reputation for brittleness. Nineteen twenty-nine saw Willys drop to 4th place in sales, and fell further to 6th in 1930. As the Depression sunk to its depths in 1931, Willys’ volume was a tenth of what it was 3 years prior.

Whether it was a sense that the good times could not last, or just pure luck, in the middle of 1929 John North Willys abruptly sold all of his common shares in Willys-Overland Company for a reported $25 million and resigned as president. Mr. Willys then accepted an appointment by President Herbert Hoover to be ambassador to Poland in 1930. In his absence, depressed conditions carried his former company toward bankruptcy. Willys-Overland lost $35 million from 1930 to 1932.

JNW returned to his company to steer it out of receivership. Despite terrible business conditions and little money, by 1933, Willys was still able to develop and introduce its new Model 77. The 77 was an all-new design that furthered the Whippet ideal of a well-made, light weight car with excellent performance. This was also perhaps the first “streamlined” automobile in America. It had a sloping hood line, swept-back grill and integrated headlamps. The Chrysler Airflow of 1934 is usually cited as being America’s first mass-produced car to incorporate aerodynamic design principles. The Airflow did take streamlining to an extreme. But the Willys 77 may have been overlooked because it wasn’t really mass-produced. The few batches had to be done so with permission from the bankruptcy court. Only 6,500 77s were built in its first year.

Willys Model 77 (www.GasserPlans,com)

Mr. Willys’ tireless efforts to save his company were eventually successful, though he never saw the fruits of his labors. After a third of a century in the auto business, from its touch-and-go beginnings, through a meteoric rise, peppered with periodic and bloody shakeouts, John North Willys was there. As one of the pioneers, he might not have liked where the industry was headed, dominated by a few large players, as the great Independents one by one fell aside. He was spared that particular indignity but not the ultimate one. In the summer of 1935 John North Willys died at his home in Bronxville, NY of a massive heart attack.

Resurrection

While men have but one life, companies can have many. Willys-Overland was almost cat-like in this respect. Soon after Mr. Willys’ death, a group of investors, led by long time sales executive Ward Canaday, was able to secure management control over the company and have its debts wiped away. Amongst his early moves at the helm, Canaday brought in three men who would lay the company’s foundation for the next dozen years.

Ward Canaday

The first was an innovative free-lance designer named Amos Northrop. Northrop had been design chief for Willys in the late 1920s where he penned the beautiful Willys-Knight Model 66 Roadster. He left to do the progressively more stunning 1931 REO Royale and 1932 Graham Blue Streak. Now back at Willys, Northrop took a bold approach on a shoestring budget. He widened the frame of the old Model 77 and gave it swept back fenders and a bold, thrusting nose. The result was the Willys Model 37. Northrop is perhaps best known for his “Shark Nose” Grahams. Comparing the two side by side suggests the Willys may have been an early “sketch pad” for the more radical car.

Willys Model 37 (www.wokr.com)

Graham Shark Nose (www.Shannons.com.au)

Joseph W. Frazer was hired to bring the Willys 37 to market. Previously Frazer had been a top sales executive at Chrysler Corporation, where in the late twenties he guided both the Plymouth and DeSoto brands into existence. The low-priced, well-engineered Plymouth arguably kept its parent afloat through the turbulent depression years. Frazer positioned the new Willys as a practical alternative to Detroit’s “colossuses.” The 37 got up to 35mpg and was advertised as using “Half the gas…twice the smartness.”

Willys’ sales quadrupled to more than 51,000 that year. Profits swelled to $500,000. Willys’ sales were still a fraction of Whippet’s heyday, but things were looking brighter as the Great Depression finally began to loosen its grip on the nation.

The third pillar of Canaday’s efforts was coxing an engineer over from Studebaker named Barney Roos. Roos had designed the legendary 9-bearing strait-eight engine that powered the magnificent Studebaker Presidents. In the decade or so since Willys’ tried-and-true 4-cylinder engine debuted in the Whippet, it had acquired and additional 13hp, now up to 48. Impressive, but enough if the Model 37 was going to succeed as a viable alternative to Detroit’s ever more powerful machines. Roos took the little 4-banger and upped the compression, added a better carburetor and camshaft, maybe even said a few magical incantations. Output was boosted all the way up to 60hp. The new engine was said to “Go like the Devil,” which gave it its name. The Go-Devil Four would power Willys’ products for two more decades, including the Jeep.

Go Devil Four (www.AllPar.com)

The Go-Devil first made its debut in the updated 1941 Willys Americar. The Americar’s shape was even more slippery than the Model 37 on which it was based. With 20% more horsepower now on tap, it was also faster.

And the Americar would go faster still. Its wind-cheating shape and low mass, combined with a spacious engine bay, made it a favorite starting point for drag racers, who swapped in flathead Ford V8s to make Americars really go like the Devil. Willys were legendary during Southern California’s “Gasser Wars” of the early 1950s.

Despite the efforts of Canaday and his team, many customers were still wary of Willys’ multiple flirtations with extinction. Of all the major U.S. car manufactures in 1941, Willys ranked ahead of only Lincoln.

Nevertheless, sales were sufficient to keep the doors open until new military contracts could be signed. Then, after the war, a new Willys savior would arrive home from the front.

Copyright@2017 by Mal Pearson

This is the first of a series on Willys-Overland-Jeep