3-Wheeling with Davis

/The Davis Motor Car Company was founded in 1946 in Van Nuys, CA, an industrial city near Los Angeles. While Van Nuys was a long way from the auto-making hub of the Midwest, the area was at the heart of the budding aerospace industry. Southern California was also the birthplace of the Hot Rod culture. Rockets and rods, both would play key roles in the story of this curious little car.

The origins of the Davis date back to the late thirties and the incipient SoCal racing scene. One of its patrons was Joel Thorne, Jr., a 20-something heir to the Pullman family fortune. Along with a virtually unlimited source of funds, Thorne had a reckless nature and an addiction to speed. Naturally he was drawn to auto racing. He set up Thorne Engineering in Burbank, CA to build racing cars that would campaign at the Indianapolis 500. A Thorne Engineering car driven by George Robson would eventually win the first post-war 500 in 1946.

Joel Thorne, Jr.

Frank Kurtis

Thorne’s shop foreman was a young man named Frank Kurtis. Kurtis would go on to build his own racing cars and become one of the all-time greats of Gasoline Ally. Kurtis-Kraft cars took the checkered flag 6 times during the 1950s. He was also renowned for his hot rods and custom sports cars. While still with Thorne Engineering, the boss asked Kurtis to build him a car for his personal use that was like nothing else on the road. War was in the air, meaning that very soon there would be no more racing. Thus Frank Kurtis turned his considerable talents to making a wild creation for Mr. Thorne called the Californian. It was a 3-wheeled roadster powered by a Mercury flat-head V8. Thorne loved it. He drove this crazy machine for the duration of the war, crashing it a few times along the way.

Gary Davis and The Californian

“The Future of the Automobile”

Glen Gordon “Gary” Davis was a charismatic former car salesman from Indiana. He had come to Southern California promoting himself as an industrial designer, though the claim seemed to be more talk than deed. There he struck up a friendship with Mr. Thorne, and by means not completely clear, acquired the Californian roadster in late 1945.

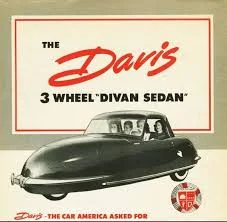

The war was over. After nearly four years of car deprivation, keeping old rides going with spit and bailing wire, Americans were clamoring for automobiles, any automobile, so long as it was new. Davis, a born promoter, saw the Californian roadster as an opportunity to market his own vision of the Future of the Automobile. That future would consist of three wheels, four-across seating and 50mpg, all for under $1,000. It all sounded too good to be true.

While Mr. Davis’ industrial design credentials may have been in doubt, his skills as a promoter were on full display. He was able to secure feature stories on “his” car in Business Week, Life and Parade magazines. Frank Kurtis was never mentioned in any of the stories. The roadster also made regular appearances in an early and short-lived TV detective series called The Cases of Eddie Drake.

Between Joel Thorne’s crashes and Gary Davis’ promotional activities, the original Californian was beginning to disintegrate. Davis was able to convince a group of talented engineers from the aerospace industry to design and build a new prototype. He enrolled them into working without pay, on the promise that they would receive double their normal salary once the car reached production. That first prototype was called the Baby. Davis arranged to have Baby lead the Tournament of Roses Parade in Pasadena on New Year’s Day 1948.

Davis design studio in Van Nyes

The publicity blitz succeeded in generating a barrage of requests – to buy the car, to invest in the company, to get a dealer franchise. Funds from investors and franchise fees started rolling in. The money allowed Davis to lease a former military aircraft plant near Van Nuys airport to assemble the car. They also funded lavish publicity tours, as well as a generous salary for Mr. Davis.

Besides the 3-wheel setup, its 4-across seating, and aluminum body panels, the Davis had one more unique innovation. There was a built in jack for each of the 3 wheels. These were fabricated out of military surplus hydraulic cylinders and lifted the car by flipping the appropriate switch.

While the Davis Baby looked unlike any other car on the road, its main underpinnings were quite ordinary. Most key components were bought “off the off the shelf” and used by other independent manufacturers, like the 63hp Continental 4-cylinder engine, Borg-Warner 3-speed transmission and differential and steering gear by Spicer.

The Baby had 4-Across Seating

Much attention was paid to the jet-age aluminum body and tubular space frame. But when a second prototype, called the Delta, was built, aluminum was abandoned for a more a conventional (and cheaper) channel steel design. The name Divan did not appear until the third car. It was part of a production run lasting slightly longer than the life span of a fruit fly, totaling just 11 cars.

One of 11 Davis Divans

Too Good To Be True

Davis had reportedly collected $1.2 million from over 300 would-be franchisees. But, while Davises were appearing on magazine covers everywhere, that seemed to be the only place they were showing up. By early 1949, the Los Angeles County DA was investigating complaints of franchise fees paid with no deliveries of actual cars. Gary Davis also faced fraud charges lodged by 17 employees who had not been paid.

Desperate, Gary Davis ordered several prototypes of a light reconnaissance vehicle aimed at the U.S. Army. It was a last ditch attempt to rescue his company with a government contract. This came to nothing. The company was seized and liquidated in November 1949.

Davis Light Reconnaissance Prototype

Despite the tiny number of Davises produced (or perhaps because of it) the 3-wheeled roadsters have a fanatical following. The Davis Registry was created in 1993 by Tom Wilson of Ypsilanti, MI to serve as a clearinghouse for information on the total of 16 Davis vehicles built. Only one Davis didn’t survive. It was destroyed by British customs. The car was shipped there in 1949 in order to generate interest. But by then the sharks were circling. Davis did not have the money to pay British import duties and the promotional car was destroyed per British law.

By 1953 Gary Davis had exhausted his appeals and was sent to a minimum-security prison for 2 years. After his release, he stayed in the car business…kind of. Davis went on to develop the Dodge-em bumper cars and Start-O-Car amusement rides. After that he started a company called Engineering Associates. He was looking for investors to build a 3-wheeled safety car, which used 360-degree rubber bumpers to cushion impacts, when he died of emphysema in 1973.

Gary Davis making raspberries

Copyright@2017 Mal Pearson