The DeSoto Airflow: Ahead of It's Time and Left Behind

/The History of the Automobile is littered with tales of cars so advanced that they flopped. Their technological or stylistic achievements were greeted in the marketplace with hesitation and suspicion. Trailblazers paid the price for being first. The 1962 Oldsmobile Jetfire was the first car to use turbocharging, delivering big block power from a smaller more efficient engine. The Jetfire flamed out after 2 years, but a decade later Turbo Saabs and Buick T-Types made inter-cooling cool. The versitile Scout Scarab of 1936 was the first minivan. After selling a total of 9 copies, it was the last one for 45 years before the Plymouth Voyager took suburbia by storm. Honda’s 60mpg Insight in 1999 introduced us to gas-electric hybrid technology. The Insight barely achieved 4-didgit annual sales, while just a few years later Toyota’s Prius would become the suburban eco-warrior’s front line weapon against climate change. And then there was the 1934 Airflow, the car that brought automotive aerodynamics into mainstream consciousness…and nearly destroyed the DeSoto brand, and the Chrysler Corporation along with it.

1934 Imperial Airflow (www.conceptcarz.com)

The story begins one summer weekend in 1927 when one of Chrysler’s chief engineers was out for a drive. Carl Breer, while touring with his family near Port Huron, Michigan, saw in the distance what at first he thought was a flock of geese flying low in the sky. As the flock drew closer it turned out not to be geese, but a squadron of Army Air Corps planes flying in formation. Breer got to thinking about how the plane’s shape helped them slip through the air with such grace and ease. Driving home, with his arm out the car window, he experimented with different angles and shapes and the way they responded to the wind. Upon his return to the office Monday morning, Breer sought out one of his engineers named Bill Earnshaw to discuss some of his conclusions. Earnshaw was acquainted with aviation pioneer, Orville Wright. At the behest of Breer and under the supervision of Earnshaw and Wright, Chrysler built the automobile industry’s first wind tunnel. Seven years later, out of that tunnel emerged one of the most significant cars in history: The Airflow.

Jaray Ley T6 (www.EcoModder.com)

Chrysler’s Airflow was not the first application of aerodynamics to the automobile. In 1921, a Hungarian named Paul Jaray went so far as to apply for patents in Germany on a streamlined car called the Ley T6. Jaray did not get far with the T6. Roads of the day did not allow the speeds necessary to make streamlining worth the trouble. A close look at the T6 suggests other factors may have had a role. Jaray’s esthetic lapses aside, by the late twenties highway improvements were such that speed had become an important selling point. A more aerodynamic shape would allow greater speed and efficiency without increasing engine size or output. With a reputation built on superior engineering, such an advance held great appeal among the engineers at the Chrysler Corporation.

1934 Chrysler Airflow (www.Allpar.com)

At the same time Airflow was given the go ahead, the decision was also made to shift DeSoto’s position in the Chrysler Corporation’s brand hierarchy. For its first five years the division was slotted just above Plymouth and roughly level with Dodge, albeit a bit spicier. For 1934, DeSoto would leap ahead of Dodge to a position just below the Chrysler brand. As a coming out party to announce its advance in status, and to give the marque a unique identity, the revolutionary new Airflow design would to be a DeSoto exclusive.

That plan would change when the man whose name is on the building took a personal interest in the Airflow. Walter Chrysler founded his company on the principal of engineering excellence. What better way to mark its first decade than with this engineering tour de force? The revolutionary new car would be a symbol of his corporation’s great technological leap. In short, the Airflow had become bigger than DeSoto. Chrysler Corporation would now offer not one but three versions of the new car. Two eight-cylinder Airflows of varying engine size, wheelbase and opulence would carry the Chrysler and Imperial nameplates, while the DeSoto Airflows would be a little smaller and lighter and be powered exclusively by sixes.

The Chrysler division hedged its bet somewhat by offering a conventionally styled six-cylinder car called the CA series, in addition to its Airflow Eights. Lower priced Plymouth and Dodge also stayed with more traditional designs. DeSoto, however, along with the top of the line Imperial, would be all-in on the Airflow.

1934 DeSoto Airfoil (www.Conceptcarz.com)

www.Allpar.com

The Airflow was like nothing that had come before it. One loses count of the car’s great leaps forward. It was not only a revolution in aerodynamics and chassis dynamics, but also in construction and interior packaging. It was the first American car to employ unit-body construction. This was essentially a space frame welded to a conventional chassis. It had 40 times more structural rigidity than its contemporaries and vastly superior handling. The engine was moved 20 inches forward on the chassis allowing a more comfortable driving position. This move allowed engineers to shift the rear seat forward off the rear axle for a more stable, less bouncy ride. As a result, it was possible to have for the first time a full width rear seat for 3-across seating.

www.Allpar.com

The car was promoted in a variety of ways. At Chicago World’s Fair, the Airflow’s handling stability was showcased as it safely maneuvered after having one of its tires shot out at speed by an Illinois State Police sharpshooter. At the Pennsylvania State Fair, Airflows were pushed off a 110 ft. cliff and then driven away under their own power, demonstrating the toughness of the unit-body design. Airflows piloted by AAA certified drivers set new records when they achieved 21.4mpg driving from New York to San Francisco, and 86.2mph on a 24hr, 2,000 mile closed course.

The automotive press sung the Airflow’s praises. Why wouldn’t they? In driving dynamics, in ergonomics and performance, in efficiency and construction, the Airflow was not only superior to every other car on the road, but even those still on the drawing board.

www.Howstuffworks.com

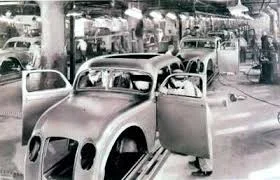

With simultaneous advances in so many different technologies, it was inevitable that problems would arise. The Airflow’s space frame required sweeping changes in Chrysler’s manufacturing process. These lead to production delays. Many early customers - those early adopters crucial to generating word of mouth excitement for a new product - grew impatient and went elsewhere. Rumors were spread by competitors that the new frames were brittle, even though the exact opposite was true.

To the engineer’s eye the Airflow was a masterpiece of form and function working in harmony. For everyone else, it took some getting used to. The car-buying public did not share seem to share the same enthusiasm for the Airflow’s art deco style as did the engineers and journalists. This was understandable. The nation was just beginning to emerge from the longest and deepest economic collapse it its history. People were not yet in a mood to take chances. And why take a chance when there was a conventionally designed Chrysler across the showroom, or a competitor across the street. Either of which could be had for 15-20% less than the complex and expensive to build Airflow.

1936 DeSoto Airstream (www.Allpar.com)

Chrysler’s sales tally ticked up only 15% in 1934, while the rebounding broader market rose by double that amount. DeSoto dealers, who did not have a conventional car across the showroom, saw sales plunge more than 20%. Credit management with quick action. A more traditional car was added to the DeSoto line in 1935. Called the Airstream, it was based on a new Plymouth/Dodge platform. It used some of the Airflow’s aerodynamic principals, but was built using a cheaper body-on-frame design. The Airstream out sold the Airflow by 3:1 that year. By 1937 the Airflow was gone from the DeSoto line.

One cannot help but wonder what would have happened had Chrysler introduced the Airstream first. As a transitional design, the less radical Airstream might have softened up the public up to streamlining before launching the more radical Airflow. The latter certainly could have used an extra year to work out the new manufacturing techniques. The American automobile might have evolved quite differently had Chrysler eased into the concepts of aerodynamic design. Sometimes its better to be the tortoise.

1934 DeSoto Airflow at the Gilmore Museum with 1932 DeSoto in background

Copyright@2019 by Mal Pearson